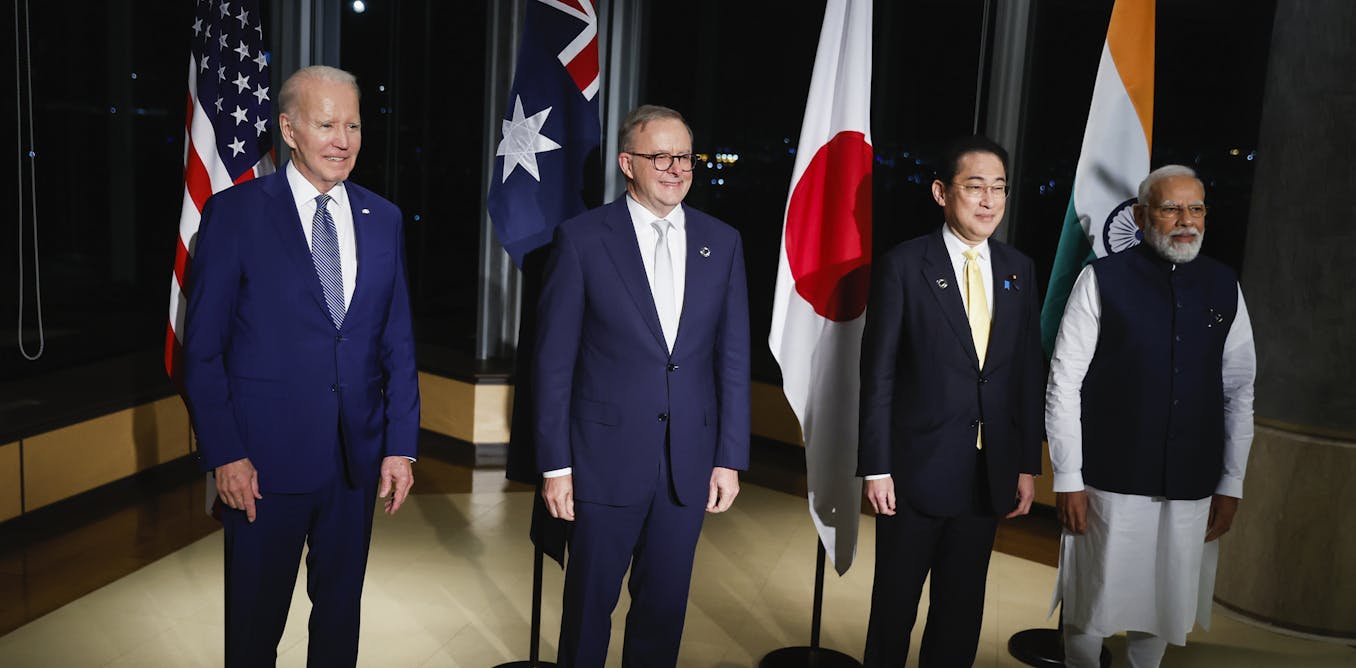

This weekend, the Quad’s 4 leaders will meet again, this time in U.S. President Joe Biden’s hometown of Wilmington, Delaware. The summit can even be a farewell for the two leaders—one of Kishida Fumio’s final acts as Japan’s prime minister, and Biden will end his term 4 months after the meeting.

The Quad is an ambitious undertaking. As the 4 explained in a lengthy first Leaders’ messageIts aim is to advertise “a free, open, rules-based order, rooted in international law and unfettered by coercion, to enhance security and prosperity in the Indo-Pacific region and beyond.”

Described by policy pundits as “minilateral” to tell apart it from broader multilateral regional institutions akin to ASEAN and APEC, the organisation brings together a small group of self-proclaimed “like-minded” countries committed to pursuing a typical set of ambitions for the world’s most populous region.

First established in 2007, the Quad brought together 4 partners to debate shared security concerns raised by China’s rising power. Its first iteration was led largely by Washington and Japan, with Australia and New Delhi being reluctant participants. The group was largely abandoned by its members in 2008. They saw little profit in such overtly anti-Chinese coordination at a time when China’s foreign policy remained cautious.

The quad was brought back to life in 2017The 4 now share a grim assessment of Asia’s geopolitical circumstances. Xi Jinping’s China has an ambitious and assertive foreign policy that has unsettled the region and prompted the 4 to dust off the Quad structure.

Andres Martinez Casares/EPA/AAP

The first formal meeting took place on the sidelines of the East Asia Summit in 2017. This was followed by a series of senior officials’ meetings in 2018 and at the level of foreign ministers in 2019 on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly. Further ministerial meetings were held in 2020 in Tokyo and online in early 2021.

Biden hosted the first leaders’ meeting of 2021. There, the group pledged to carry an annual event to offer lasting political momentum for a gaggle the 4 now see as critical to their interests in the region.

At first, the Quad focused on military cooperation to advertise shared military concerns. However, in a comparatively short time, it has moved away from this security focus and has now developed a broad scope of activity. The group has established work programs on climate change, public health, immunization, high technology, infrastructure, educational exchanges, maritime domain awareness, humanitarian assistance and disaster relief, and even space.

Although it has never been explicitly stated, the Quad is anxious with managing a collective response to China’s rise. The 4 are concerned about the military dimensions of Beijing’s growing prosperity, but in addition about the larger threats to the region’s operating system that this ambitious authoritarian power represents. While military concerns prompted the Quad’s creation, these latter concerns at the moment are being debated.

Oddly enough, economics should not currently part of the equation. This is a noticeable flaw given the ways China uses geoeconomics to advertise its interests.

The Quad re-emerged on the international stage greater than half a decade ago. It quickly went through all the gears, becoming a “leader-led” group, with the attendant media attention and a dramatically expanded policy scope. Despite its impressive statements and long list of work priorities, the reality is that the group has achieved little in terms of concrete cooperation.

As an exercise in diplomatic signaling it was remarkable, and in international affairs symbols matter, but only up to a degree. The achievement of practical cooperation was limited, as was its impact on the regional strategic balance.

Although grouping is clearly a priority, countries are still not particularly well-prepared to work as a quad. This is a function of basic experience in addition to bureaucratic constraints. With time and investment we will expect improvements, but it can be crucial to notice that this has not happened thus far.

If Quad members want their cooperation to be, as a recent article put it, Ministerial Statement “provide concrete benefits and act as a force for good,” then the group must engage in actual political cooperation.

Another major challenge is ensuring that the 4 countries align their interests in the future. All have concerns about China’s growing influence, but beyond that there are some serious challenges in keeping the group together. This is most blatant in relation to Russia, where India’s approach to Moscow is at odds with that of the other three. And their divergent approaches to their economies also make cooperation on this front extremely difficult.

When the leaders gather in Delaware, expect rather a lot of platitudes about the departing American and Japanese leaders, in addition to a fair more elaborate set of agendas to work on. There will be plenty of oblique references to the China challenge and lofty rhetoric. But until the Quad gets going, its ability to exert influence beyond optics will be limited.