Education

Contrary to public opinion, most black parents are involved in their children’s education

Following recent clips circulating on social media highlighting black students’ learning gaps or lack of parental involvement, Ashley Thomas, an Indianapolis parent advocate and mother of three, says that is removed from the reality for a lot of black parents.

“A lot of times, a lot of us as Black parents, we hear negativity when something bad happens, or, ‘Oh, these parents aren’t showing up,’” Thomas said. BLACK ENTERPRISES.

“We’ve seen numerous TikToks about what parents are doing, but parents are doing the whole lot they will and so they’re literally changing the sport… and we’re patting parents on the back for that and saying, ‘Hey, that drum beat, you possibly can keep doing that.’

A brand new report from the United Negro College Fund (UNCF) entitled “Hear Us, Believe Us: Centering the Voices of African American Parents in K-12 Education.” confirms Thomas’s feelings with research on the subject offers a comprehensive evaluation of experiences, challenges and aspirations African American parents on race, college aspirations, parental involvement, and more.

“We are really excited about this work and the opportunity to elevate parent voices because too often we know that parent voices are silenced, but we know that they have been making a difference in education for decades,” said Dr. Meredith BL Anderson , said UNCF Director of K-12 Research TO BE.

Although UNCF just celebrated its eightieth anniversaryvol anniversary of highlighting minority students pursuing higher education, the organization also has K-12 Advocacy shoulder to ensure the subsequent generation is college ready.

“For the past 12 years, we have been elevating the voices of the Black community on a variety of issues related to K-12 education, from race to college readiness to equity,” Anderson said.

“So my role is to produce research reports, talk to community members – whether they’re parents, students, counselors, teachers – and make sure that we’re dismantling some of these deficit narratives when it comes to our Black communities, because we know that they are engaged, informed and ready to make a difference.”

UNCF’s Advocacy Division creates college preparation tools and has over 20 publications and resources on the elementary and middle school levels alone. The latest report, released May 2, highlights the critical role African American parents play in their children’s education. It emphasizes the importance of understanding their unique perspectives and incorporating them into educational policies and practices.

UNCF conducted the study on a national sample of black parents using telephone surveys and focus groups. The study also oversampled black parents in Chicago, Indianapolis, Atlanta, Houston, New Orleans and Memphis. Some of the important thing ones report arrangements include:

- Black parents report higher academic aspirations for their child and fewer school suspensions when more Black teachers work in their child’s school. For black parents and guardians whose children attended schools where many or most of the teachers were black, the likelihood that their child received exclusionary discipline is sort of 3 times lower than when their child attended schools with fewer black teachers.

- Black parents highly value higher education and are deeply involved in and invested in their children’s education with 84% of black parents feeling it is crucial for their child to attend and graduate from college, and over 80% checking their child’s homework and talking to their child’s teacher repeatedly. Meanwhile, 93% of Black parents say they need more opportunities to be involved in their child’s education and have input on education laws.

- Black parents want to see more Black leaders in education. Seventy percent of African American parents and guardians consider that involving African American leaders and organizations will make school improvement efforts more practical.

- School safety is a key issue for Black parents and caregiverswith 80% of African American parents and guardians rating safety because the most necessary factor when selecting a college.

Dr. Anderson emphasized that the report focuses on the importance of Black teachers.

“We also found that black parents felt more respected when there were more black teachers. So we know that Black teachers are important,” she said.

The report concludes with a series of recommendations designed to address the concerns and aspirations of African American parents.

Recommendations for the K-12 sector

- Invest unapologetically in Black teachers.

- Create more intentional opportunities for parent involvement.

- Create a learning environment that reflects African American history and culture.

- Partner with local organizations to provide resources and services for families.

- Value and treat support staff in school budgets.

- Prioritize student safety.

Recommendations for higher education

- Make intentional efforts to provide students and families with college opportunities.

- Create intentional pipelines of collaboration with districts and charter organizations to increase teacher diversity.

- Ensure teacher training programs include anti-racist and culturally relevant teaching practices.

- Collaborate with K-12 schools and districts to provide students and families with financial and literacy resources.

For Thomas, an Indianapolis parent advocate, her personal passion for investing in her children’s education has translated into her skilled work as founder and CEO of an organization Consulting by the ANT Foundation, which provides community organizing training, strategic community mobilization, and organizational leadership development. It encourages parents and educators to “co-parent” for their child’s educational success and to take seriously the calls to motion in this report.

“I tell parents all the time, ‘When I move, you move, that’s just the way it is.’ We need to work together in the community to make something happen. So we also need to make sure that these reports don’t just sit there; we use them to empower parents to move and have a voice at the federal level, at the state level, at the political level, at the school district level – whatever it is – because our voices are powerful.”

Access to full report here AND Tune in to stream BLACK ENTERPRISE on Friday, May 3 at noon ET platforms down podcast where Dr. Anderson discusses the report’s findings and Ms. Thomas gives parents recommendations on working with schools.

Education

Usher provides an inspiring address at the University of Emory, receives an honorary doctorate

Usher Raymond IV is officially a physician – at least honorary!

Dressed in a university blue and golden outfit, the 46-year-old R&B icon received an honorary doctorate during the Emory University school ceremony on Monday, May 12, at the School Center of Physical Education in Atlanta, where he also provided the start address, the address, the address, Atlanta Journal-Constitution Reported.

Singer “Yeah” turned to class 2025 And their members of the family for about 20 minutes with jokes about mimosa, childhood stories growing up in the capital Georgia, and inspired newly broken graduates to prosecute after their biggest dreams.

Thank you to the school for honor, Grammy winner admitted that he thought he needed one other performer when the school first reached out. He was shocked that they wanted him to produce the start address and received an honorary doctorate. He also thanked his wife, mother and kids who were present.

“I want to thank my family for being here. My wife, Jennifer G. Raymond, my children who were here, who got up well early in the morning and who were furious at me,” he irritated when he moved away from the crowd. “But it was worth it because I am a doctor.”

During his comments, he remembered that he had received a “naughty awakening” when he got here to Atlanta for the first time and went to highschool.

“In academic terms, I was so far behind that I was unable to keep up, and the school staff in which I participated had no resources to help me,” he said, adding that placing in the repair classes “I felt the judgment of my ability as a black man or child”.

However, the singer “OMG” attributed her “passion” how he was capable of overcome “misunderstanding” and grow to be a clerk that everyone knows today.

“Before I could sing, before I could dance and before I was a doctor, I had a passion,” said Usher. “The system did not know what to do with a student like me.”

This experience, as he said, eventually led him to dedicated to underestimated children through the recent Non -Profit Usher organization, which has helped over 50,000 students in the last 25 years Fox 5.

Usher gave examples of each the value of education and the numbers that increased without him, comparable to the producer and collaborator of Usher Braun, a former Emory student who never graduated from school.

“In a world where certificates can feel dim clicked, observers and algorithms, does the diploma still matter?” He asked. “Yes, of course yes. But it’s not the paper that gives power. It’s you.”

Usher turned to the crowd about 5,500 graduates and their members of the family during what meant the 100 and eightieth school ceremony. The ceremony initially took place outside, but was moved home because of the extreme weather, he gave Fox 5. Turning to the crowd, Usher gave the students check the reality of what awaits them.

“You put yourself in a world that is very different from the one I have entered at this age. I know that I do not look, but I am 46 years old,” he joked.

Apart from all jokes, he noticed that although some things are “beautiful”, comparable to technological progress, there are also some changes which could possibly be “deeply disturbing”. One of the predominant problems is education, which, as he said, is “fundamental law”, which is “politicized and minimized, and erased in some places.”

Before he wrapped, he strengthened the graduates with knowing that they were architects of the future, encouraging them to “unrealistic, a bit delusional, even in pursuit of happiness and fulfillment.”

He added: “At the same time, be patient, respect the process because life is full of challenges and they either broke you.”

(Tagstrancet) Emory University

Education

Anti-Dei Push Trump does not stop the black Kentucky hails from the celebrations outside the campus

President Donald Trump, with a purpose to eliminate diversity initiatives at university campus, did not stop minority students from issuing their very own ceremonies after the cancellation of the University of Kentucky ceremony to honor their graduates who’re black or from other historically marginalized groups.

Do it as a lesson, easy methods to think strategically to get the desired result.

Several students, decorated with hats and dresses, fucked up on Wednesday in the focal point, when their families and friends cheered them at the celebrations outside the campus. Graduates were honored for the years of educational work and received special regalia, resembling the capital and strings, which they will wear at the starting of the school this week.

The speakers presented the words of encouragement to the graduates, at the same time guided by rainfall about federal and state republican efforts in favor of the end of the end of diversity, equality and inclusion programs.

“You are accused of standing on our arms and doing larger and better things,” said Christian Adair, Executive Director of Lyric Theater, a recognized Culture Center for the Black Lexington community, where the ceremony took place.

The “Senior Salute” program was organized after the flagship Kentucky University recently canceled the ceremonies for minority graduates. The school said that it will not host the “celebration of graduation based on identity or in special interest”, citing “changes and directives of federal and state policy”.

It was then that the members of the Historically Black Alpha Phi Alpha community performed and have become the driving force of organizing substitute celebrations.

“The message that I wanted to send is that if you want something to happen, you can simply do it yourself,” said Kristopher Washington member, a key organizer of the latest event and who’s amongst the students. “There is no waiting for someone to do it for you.”

Washington said that Great Britain’s actions were disappointing, but not surprising.

“I have already understood that the institution will probably turn to its financial well-being before thinking about doing something … for students,” he said.

Most latest graduates and audience members on Wednesday were black, although the event was settled as multicultural and open to numerous students – including those that are LGBTQ+ or certainly one of the first of their families who graduated from College. Ushers were David Wirtschafter, Rabbi Lexington, who wanted to indicate his support for college kids and praised them for refusing to just accept the lack of the guild.

“Recognition for them for taking over the initiative and leadership when these unfortunate circumstances developed to organize this event for themselves,” he said.

Throughout the country, universities were under the growing pressure to affix the political program of the Trump administration, which has already frozen billions of dollars in scholarships at Harvard University and other universities, which they did not do enough to counteract what, based on administration, is anti -Semitism.

Trump’s calls to eliminate each program, which treats students in another way due to their race, brought a brand new control of the affinity completion ceremony. The Education Department really helpful universities to distance itself from Dei by letter in February. It was found that the Supreme Court’s decision in 2023 banned the use of racial preferences in admission to studies, and in addition concerned such areas as employment, scholarships and ceremonies of graduating from school.

This yr, laws dominated by Kentucky adopted the provisions regarding the breakup of diversity, justice and inclusion to public universities.

In a recent film, defending his appeal, the president of the University of Eli Capilouto said that the decision appeared at a time when “each part of our university is under the influence of stress and control.” The school said in a separate statement that it will rejoice all latest graduates during official start ceremonies.

“We made difficult decisions – decisions that cause fears in themselves, and wounded in some cases,” said Capilouto in the film. “The cancellation of the ceremony for people on our campus who’ve not at all times seen to reflect in our wider community is certainly one of the examples.

“We have taken these actions because we think it is required, and we think that compliance with the law is the best way to protect our people and our continuous ability to support them,” he added.

But his cancellation of smaller celebrations to honor LGBTQ+, black and first generation graduates, drew criticism of some students and relatives on Wednesday. Events have long been seen as a technique to construct community and recognize the achievements and unique experiences of scholars from historically marginalized groups in society.

Brandy Robinson was certainly one of the many members of the family who cheered their nephew, Keiron Perez, during Wednesday’s ceremony. She said that it is crucial for relatives to share at the moment, and she or he condemned to chop off bonds with such events as “Coward movement”.

“To tear these moments away from them, it’s just very disappointing,” said Robinson.

Asked why the event was vital for college kids, the president of Alpha Phi Alpha, Pierre Petitfrere, said: “He gives students something to remember and know that even taking into account the circumstances of what is happening all over the world, they are still recognized for hard work and fight for many difficulties that could encounter all the time in college.”

The spokesman for Great Britain, Jay Blanton, said that the school recognized “how significant these celebrations were for many”, and student groups are welcome in events with the host.

“Although the university cannot continue to sponsor these events, we will continue to work so that all students feel seen, valued and supported,” he said in a press release.

But Marshae Dorse, a graduate who took part in the Wednesday ceremony, said that the UK decided to “swipe” to the anti-dei push, calling it “a bit like a hit in the face, because something like this is so harmless.”

(Tagstotransate) lifestyle

Education

Join the conversation and help build a Black Teacher pipeline

Black teachers have a great impact on black students. Join the discussion on the retention and recruitment of black teachers.

May 8, Center for the Development of the Educator Black (CBED) Commeminely the day of the Black Teacher’s recognition, organizing the online panel, “”Building a varied teacher pipeline. “

The panel of teachers, founders and politics leaders will conduct a vital conversation about the day of recognition of the black teacher, emphasizing the urgent have to recruit and maintain various teachers throughout the country.

“This internet seminar also emphasizes the flagship CBED, Asaching Academy (TA), double -mutual program, career and technical education (CTE), designed to support the subversification of teachers and improving academic results for all students,” CBED said in a press release.

The advisable voices are Ansharaye Hines, assistant to the director for profession and technical education and curriculum at CBED; Dr. AB Spence, head of the CBED training and implementation program; and a student of the Howard Jahmere Jackson University.

CBED organizes this event as a part of the #WeneedblackTeachers campaign. The day is dedicated to celebrating immunity, commitment and overwhelming influence of black teachers. He can also be used to the recognition of a black teacher sounds alarm about a critical shortage of black teachers in the United States.

Black teachers matter

Research emphasizes the influence of black teachers on the academic success of black students. For example, black students who’ve no less than one black teacher at primary school are 13% more exposed to highschool, and 19% more often enter studies.

This percentage increases significantly with many black teachers during their school profession. Despite the advantages, only 7% of public school teachers in the US discover as black, while black students constitute over 15% of the K-12 population.

Join the ceremony

CBED encourages individuals and communities to have interaction on the day of recognition of black teachers.

Shout a black teacher – He publicly recognizes the black teacher who influenced your life, returning to recognition in social media. Use hashtags #THankaBlacktecher and #weneedblacktechers

Share the story – Create a video, post or reel emphasizing the influence of a black teacher in your life.

Join the movement – get entangled in the political process regarding education regulations. A supporter of politicians who strengthen the retention and highschool diploma of black teachers.

-

Press Release1 year ago

Press Release1 year agoU.S.-Africa Chamber of Commerce Appoints Robert Alexander of 360WiseMedia as Board Director

-

Press Release1 year ago

Press Release1 year agoCEO of 360WiSE Launches Mentorship Program in Overtown Miami FL

-

Business and Finance11 months ago

Business and Finance11 months agoThe Importance of Owning Your Distribution Media Platform

-

Business and Finance1 year ago

Business and Finance1 year ago360Wise Media and McDonald’s NY Tri-State Owner Operators Celebrate Success of “Faces of Black History” Campaign with Over 2 Million Event Visits

-

Ben Crump1 year ago

Ben Crump1 year agoAnother lawsuit accuses Google of bias against Black minority employees

-

Theater1 year ago

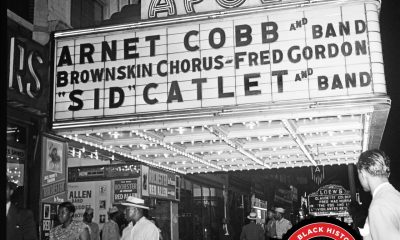

Theater1 year agoTelling the story of the Apollo Theater

-

Ben Crump1 year ago

Ben Crump1 year agoHenrietta Lacks’ family members reach an agreement after her cells undergo advanced medical tests

-

Ben Crump1 year ago

Ben Crump1 year agoThe families of George Floyd and Daunte Wright hold an emotional press conference in Minneapolis

-

Theater1 year ago

Theater1 year agoApplications open for the 2020-2021 Soul Producing National Black Theater residency – Black Theater Matters

-

Theater11 months ago

Theater11 months agoCultural icon Apollo Theater sets new goals on the occasion of its 85th anniversary