In 2020, England introduced opt-out system on organ donation to facilitate the donation of organs after an individual’s death. The Organ Donation (Presumed Consent) Act 2019 it was assumed that unless someone explicitly resigned, they’d consented to organ donation.

This change was expected to increase the variety of organ donors and ultimately save more lives. But tests by me and my colleagues reveals a unique story. Instead of simplifying organ donation, the law has created more confusion and complications. This may help explain why organ donation rates have not increased after the decline seen through the pandemic.

Before the law modified, organ donation in England required you to register on the system by registering your consent. Under the brand new system, unless an adult over the age of 18 opts out, his or her consent is presumed. However, the law is “soft”. Families should support this decision, but can overturn it in the event that they disagree, without consequences.

The law, introduced at the peak of the Covid-19 pandemic, was intended to increase the variety of donors by shifting the burden from individuals who must register to individuals who must declare that they are not looking for to donate organs or tissue. Similar regulations have already entered into force in Wales in 2015 and beyond Scotland in 2021

But the outcomes didn’t meet expectations. Consent rates for organ donation in England have dropped because the Act got here into force from 67% in 2019 to 61% in 2023. The same was the case in Wales, where the proportion of donations fell from 63% to 60.5%, and in Scotland, where the proportion dropped from 63, 6% to 56.3%.

This decline coincided with the spread of the Covid-19 virus and it is difficult to link the results of the change in law with its duration effects of the pandemic on people’s interactions with health services. However, this implies that potential organ donors don’t necessarily leave clear instructions regarding organ donation, which may impact the well-being of their families and medical staff accountable for implementing the law.

Our research included interviews with families of potential organ donors and health care professionals involved in the method. We found that many families still said they wanted to be the ultimate decision-makers, although the law required their loved one’s consent. This reflects the chance of confusion and stress in an already difficult period.

What went incorrect?

The essential issue is that presumed consent law challenges a long-standing norm in health care that emphasizes explicit consent, and particularly the role of family consent. This departure from established ethical practices has placed healthcare staff in a difficult position. They now face a dilemma – they need to comply with the law and increase the variety of organ donations, but at the identical time they risk being perceived as crossing ethical boundaries by “removing organs” without the express consent of the family.

The fear of being seen as disregarding the emotions and rights of bereaved families has led to high levels of risk aversion amongst those accountable for implementing the law. As a result, consent processes have gotten more complex and careful. This undermines the unique purpose of the Act.

However, a compassionate understanding of the situation is essential. The risk aversion adopted by official bodies is just not a scarcity of intention, but a mirrored image of the moral and emotional complexities surrounding organ donation.

Well-intentioned legal changes, while theoretically sound, have faced practical challenges in balancing the law with respect for the sensitivities of bereaved families.

The expected increase in organ donations didn’t occur. While the pandemic may have played a task on this, our research suggests that legislative changes alone are insufficient unless we address underlying ethical tensions and the necessity for clear, compassionate communication with families in such difficult times.

Many of the families we talked to I didn’t fully understand concept of presumed consent. A choice to donate is assumed here unless the person has actively opted out. In some cases, families have struggled with the considered their loved one undergoing surgery, losing sight of the potential life saved by organ donation.

The process was also overwhelming. Families had to take care of complex consent documents and lengthy procedures, which added to the emotional burden of losing a loved one.

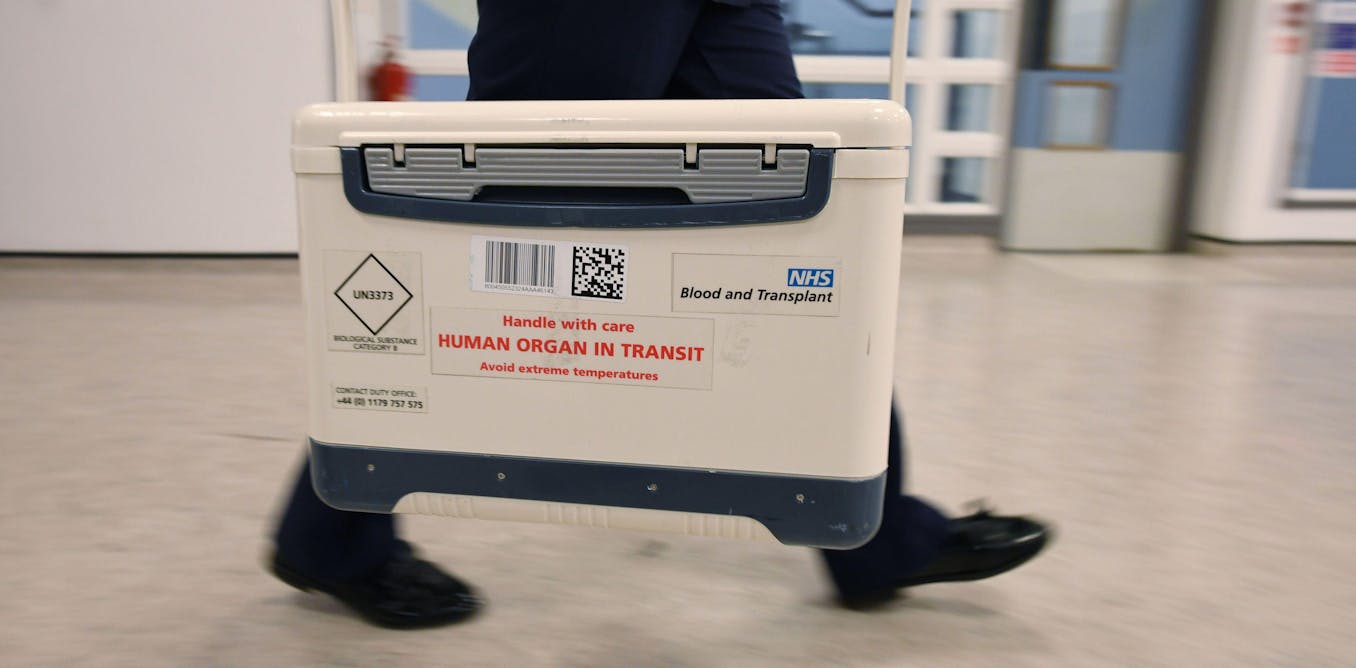

Kmpzzz/Shutterstock

What needs to be modified?

Our research suggests several possible ways to improve the system. Better public understanding is important. More explicit public education campaigns are needed to explain to people how the opt-out system works and to health care providers concerning the importance of discussing the choice to donate organs with members of the family. Many people still don’t understand that in the event that they don’t opt out, they’re assumed to have consented.

This process also needs to be simplified. Reducing the “consent” steps involved in organ donation would help ease the burden on bereaved families.

Strengthening donor decisions can even assist in this example. Giving more legal weight to decisions you make in life, reminiscent of registering for Organ donor registercould prevent families from changing their family members’ wishes.

It is very important that healthcare staff are properly trained. Nurses and doctors need higher training to navigate the complexities of the law in order that they might help families with conversations about organ donation.

Regular reminders encouraging people to update their organ donation preferences might help ensure families are aware of their family members’ wishes, reducing confusion at critical times. Only then can we hope to increase organ donations and achieve the goal of saving more lives.