Sports

Historically, Miami’s Black Coconut Grove has nurtured young athletes. Now that legacy is at risk

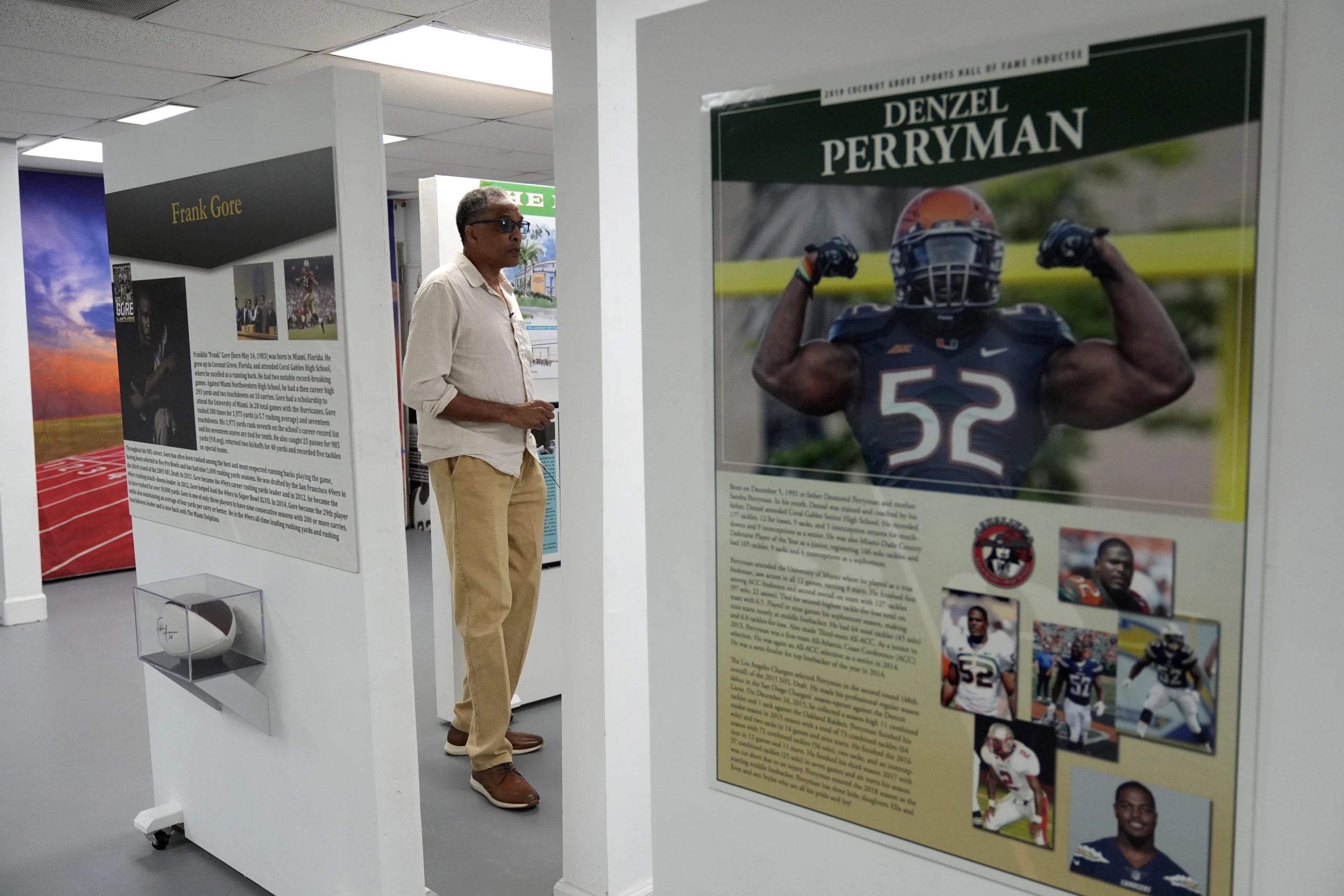

MIAMI (AP) – Amari Cooper’s football jersey hangs within the Coconut Grove Sports Hall of Fame. The same goes for Frank Gore, in addition to tributes to Negro League baseball player Jim Colzi and football coach Traz Powell, whose name graces arguably essentially the most respected highschool football stadium in talent-rich South Florida.

They represent West Coconut Grove when it was a majority-Black neighborhood hidden amongst Miami’s wealthiest areas that thrived on family-owned businesses, local gatherings and sporting events. Some call it West Grove, Black Grove or Little Bahamas, referring to its roots. Most simply call it The Grove, a spot steeped in cultural history transformed over the a long time.

“When you talk about what The Grove is, you’re talking about the real history of South Florida,” said Charles Gibson, grandson of certainly one of the primary black members of the Miami City Commission, Theodore Gibson.

Sport was his heart. It has supported the early careers of Olympic gold medalists and football stars like Cooper, national champions and future Football Hall of Famers like Gore, who make their first sporting memories on this close-knit community.

Today, there are few remnants of this proud Black heritage. Years of economic neglect followed by recent gentrification have destroyed much of the realm’s cultural backbone. Vigorous youth leagues and sports programs have dwindled. Now the community that once created an environment during which young athletes could succeed – a trusted neighbor caring for a young soccer player heading to training, a respected coach instilling discipline and perseverance in a future track and field star – is at risk of extinction.

“I think in two or three years, if something isn’t done, Black Grove will be completely destroyed,” said Anthony Witherspoon, a West Grove resident and founding father of the Coconut Grove Sports Hall of Fame.

Witherspoon, known by everyone on the town as “Spoon,” is a former college basketball player and coach who returned to West Grove in 2015 after nearly 30 years in Atlanta and located a neighborhood much different than the one during which he grew up .

Witherspoon recalls the late Nineteen Seventies, when he walked down the aptly named Grand Avenue — once the economic epicenter of West Grove — after a Friday night highschool football game, dined at a neighborhood mom-and-pop joint and frolicked at the favored Tikki Club.

Earlier generations in the realm died, lots of their families moved elsewhere, and disinvestment led to poverty and neglect. Redevelopment then kicked in, replacing longtime residents with non-black newcomers. Mommies and daddies have largely disappeared. The same goes for Club Tikki, currently an empty constructing with the last vestiges of vibrant Bahamas-inspired colours on the partitions.

“I was here. I lived in the community. I felt the influence of sports,” Witherspoon said. “I got here back from Atlanta, Georgia, and I used to be exposed to gentrification. In the back of my mind, I had this thought: We still must protect this history.

Witherspoon founded the Hall of Fame to maintain that legacy alive. A time capsule of roughly 90 area athletes and coaches, it begins with characters like Colzie, a World War II veteran who played baseball for the Indianapolis Clowns of the Negro Leagues, and ends with former pro running back Gore and Cooper, a receiver from Cleveland Browns.

“Coconut Grove is a nesting place for all of us athletes in this area,” said Gerald Tinker, a West Grove resident who won a gold medal within the 1972 Olympics as a member of the U.S. 4×100-meter relay team. “They would always expect us to be just as good (as previous generations) and just as humble. And it’s always been like that.”

The community’s status for athletics was born at George Washington Carver High School, a segregated black school. Carver was a football powerhouse within the Fifties and Nineteen Sixties, winning five state championships under Powell, who helped shape the landscape of Miami’s highschool sports scene.

Harold Cole, a former coach and athletic director at nearby Coral Gables High School who was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 2019, said Powell’s influence lasts for generations.

“He was a coach; he was a mentor,” Cole said. “He was responsible for many of the athletes who came out of Coconut Grove.”

Cole said West Grove still has youth sports programs, but since many families have moved away and kids have gone to other school districts, “it’s not the same anymore.”

Integration within the Nineteen Seventies forced Carver to shut. It is now a junior highschool positioned within the affluent nearby town of Coral Gables.

“This division to some extent broke the fabric of the community in the 1980s.” Witherspoon said.

Nichelle Haymore’s family hopes to preserve a part of the old neighborhood by reopening the Ace Theater, a preferred venue for black residents through the Jim Crow era. Haymore’s great-grandfather, businessman Harvey Wallace Sr., bought the Grand Avenue theater within the Nineteen Seventies. Born in West Grove, Haymore spent years in Texas before returning in 2007 to assist maintain the theater.

“The atmosphere of the area is different,” Haymore said. “Neighbours, who may have taken care of your home at the beginning, don’t greet each other or talk. People are walking their dogs in your yard. This neighborly respect is different because the neighborhood is different.”

Shotgun-style homes owned by black residents were torn down in favor of sleek, boxy developments – some called ice cubes – and apartment buildings far too expensive for the middle-class individuals who built the community. Abandoned, boarded-up buildings stand in places where they once attracted crowds. Giant real estate advertisements hang on the fences of empty plots.

“They’re tearing down homes that have been in families for years and building row houses,” said Denzel Perryman, a Coconut Grove resident and former University of Miami star who played as a linebacker for the Los Angeles Chargers. “So it has an impact on the community because some kids from there are going to different places and parks because they don’t live in the Coconut Grove area.”

Perryman, who lived in Miami’s historic Black neighborhood of Overtown as a baby, spent most of his time in West Grove, playing football at Armbrister Park or participating in the numerous extracurricular activities the community offered.

Featured Stories

Some still exist today. Perryman watched his childhood football team, the Coconut Grove Cowboys, win the Pop Warner championship in December. Youth teams still train at Armbrister Park, although a few of them look different to groups from years ago.

“It’s unfortunate because you lose so much, character,” said Gibson, a football and lacrosse coach. “There are certain things locally that are related to family. When you lose that, I feel it’s sadness.

Gibson, like many other residents, is determined to support the identical family environment that raised him.

“You can’t put a dollar sign on a sign that says, ‘Go to grandma’s house. She (lives) next door,” Gibson said. “You don’t even have to look outside because you know it’s only 10 steps away and they’re home. How can you put a price on it?”

In The Grove – individuals are trying to search out the reply to this query – before it is too late.

Sports

NFL star Terrell Owens signs a contract with Michael Strahan’s talent agency

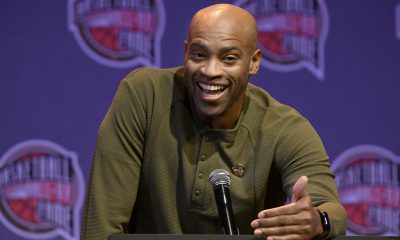

NFL Hall of Fame receiver and podcast host Terrell Owens has signed with a talent agency to further strengthen his claims within the entertainment game.

According to , Owens was signed by SMAC Entertainment, headed by host and NFL Hall of Famer Michael Strahan and his business partner Constance Schwartz-Morini.

NFL insider Jordan Schultz has also joined SMAC Entertainment.

“We are excited to add TO and Jordan to the SMAC family. They are both at the top of their game and set the standard in their industry,” Schwartz-Morini said in a written statement. “TO and Jordan have already brought an infectious energy to our team, and we are excited to help them realize their vision for careers in media, business and branding.”

A five-time first-team All-Pro and six-time Pro Bowler, Owens played for the San Francisco 49ers, Philadelphia Eagles, Dallas Cowboys, Buffalo Bills and Cincinnati Bengals. In 2018, he was finally inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

A member of the 2000 NFL All-Decade Team, Owens finished his profession with 1,078 catches for 15,934 yards, 14.8 yards per catch and 153 touchdowns, rating third all-time in receiving yards and touchdowns.

Since retiring from skilled soccer in 2012, Owens has already made several moves. He has appeared in several movies and tv shows, including “,” and in addition had his own reality show, “, on VH1.

He currently co-hosts the podcast with former NFL player and sports analyst Shannon Sharpe.

SMAC Entertainment is home to stars similar to rapper and actor Common, Wiz Khalifa, Strahan, Deion “Coach Prime” Sanders and current NFL players similar to Stefon Diggs and DK Metcalf.

Sports

Phoenix Suns guard Devin Booker brings an NBA championship desire with his Olympic experience

The gold medal went to the USA Basketball team. Mission completed on the 2024 Paris Games. U.S. men’s basketball coach Steve Kerr just answered his final query during his final news conference on Aug. 10 after his team defeated France within the gold medal game.

However, before leaving the stage of the press conference in Paris, Kerr stopped to deliver an unsolicited message to media around the globe.

“Devin Booker is an amazing basketball player. Nobody asked about him. He was our unsung MVP. I just desired to say that,” Kerr said.

The “underrated MVP” compliment meant so much to the Phoenix Suns guard.

“It meant everything. No one really asked him,” Booker recently told Andscape. “That was probably something that was weighing on his mind throughout the entire process. A 12 months ago I said what I desired to do for this team and what we desired to do for the country.

“It was a lot larger than all of us. Survival was something we’d discuss for the remainder of our lives.

The USA Basketball team was centered around NBA star icons LeBron James, Stephen Curry and Kevin Durant. There has also been some discussion amongst media and fans in regards to the lack of playing time for Jayson Tatum and, to a lesser extent, Tyrese Haliburton. Lost within the shuffle was the all-around, unselfish play of sharpshooter Booker wearing the armband.

Daniel Kopatsch/Getty Images

Booker was fourth in scoring for the U.S., averaging 11.7 points, 3.3 assists and a couple of.2 three-pointers made early in all six Olympics, and likewise had the perfect plus/minus (plus-130) for an American. Kerr was impressed with Booker’s deal with a difficult defense, regardless that he is thought for his offense, ball movement and the way he has adjusted to not being one in every of the highest options on offense.

“I just understood what was at stake,” Booker said. “I’m proud to be from this country. I’m happy with playing basketball. Even though it wasn’t invented in America, we dominated for a very long time. Obviously the world is incredibly talented and the sport is growing, however it was just one other message to allow them to know who we’re.

Booker said he also learned in regards to the preparations from his all-star team, watching the preparations on and off the court. The 28-year-old added that he gained lifelong friendships.

“It’s cool to see that everyone has their own issues,” Booker said. “In my 10 years in the NBA, I’ve learned that you have to choose what you can use for yourself. But the level of detail, the attention to detail, the intensity – it’s all consistent across the board.”

As for Durant, Booker said the bond between the 2 Sun stars “is close and grows stronger every day.” They live about five minutes from one another within the Phoenix area and commonly spend time at home and on the road. Most recently, Booker had to steer the Suns without Durant, who was sidelined with an injury.

The amazing Durant averaged 27.6 points, 6.6 rebounds and three.4 assists, which were tops for the Suns. However, the 14-time NBA All-Star has been sidelined since November 8 with a left calf strain. Suns players Bradley Beal (calf) and Jusuf Nurkic (ankle) were also sidelined. The Suns are 1-5 without Durant, which incorporates 4 straight losses.

Booker and Suns sans Durant’s next rivals shall be the New York Knicks on Wednesday evening (ESPN, 10 p.m. ET). Over the last six games, Booker is averaging 24.1 points, shooting 43.2% from the sphere and making 16 of 43 three-pointers. Suns guard Tyus Jones said there was numerous pressure on Booker offensively due to the injury.

“We’re asking a lot of Book,” Jones said after Monday’s 109-99 loss to the visiting Orlando Magic. “It’s numerous pressure for him. We are very focused on it. They are physical with him, holding him and grabbing him, throwing two or three bodies at him all night long. So he’s got so much on his plate and we just need to proceed to seek out ways to get him open within the moments we will and proceed to assist him when other players are taking shots and making plays.

Adam Pantozzi/NBAE via Getty Images

Booker currently has two Olympic gold medals, 4 NBA All-Star appearances and one NBA Finals appearance. The only thing missing from the Suns’ second-leading all-time scorer is an NBA championship. Since the Suns joined the NBA as an expansion team in 1968, they’ve yet to win a title.

After experiencing the joys of winning a gold medal, Booker as an NBA champion wants the gold Larry O’Brien NBA Championship Trophy much more.

“Most of the guys that were there did it,” Booker said of his Olympic teammates who were NBA champions. “They were champions. This is standard for them. Anything lower than that, they need nothing to do with it. It’s contagious…

“That’s all I want. That’s all I want.”

Sports

New Unrivaled Women’s League Reveals Team Rosters and Coach Allocations

After months of introducing the players and coaches who will participate in its inaugural season, the brand new Unrivaled 3-on-3 women’s basketball league announced its team rosters and coaching assignments on Wednesday.

Founded by WNBA players Napheesa Collier and Breanna Stewart, Unrivaled consists of six teams of six players each. The league was created to offer WNBA players with a substitute for playing overseas in the course of the offseason.

Although initially announced as having 30 players, the league has since expanded to 36, which Collier attributed “above financial forecasts”. The league has announced 34 players publicly up to now.

The inaugural season of Unrivaled will begin on January 17, 2025, with all games going down in Miami. Here are the official teams for the inaugural season, as well season schedule.

Vinyl Basketball Club:

– Coach: Teresa Weatherspoon

Rose Basketball Club:

– Coach: Nola Henry

Mgła basketball club:

– Coach: Phil Handy

Lunar Owls Basketball Club:

– TBD: wild card

– Coach: DJ Sackmann

Phantom Basketball Club:

– TBD: wild card

– Coach: Adam Harrington

Laces Basketball Club:

– Coach: Andrew Wade

-

Press Release8 months ago

Press Release8 months agoCEO of 360WiSE Launches Mentorship Program in Overtown Miami FL

-

Business and Finance6 months ago

Business and Finance6 months agoThe Importance of Owning Your Distribution Media Platform

-

Press Release7 months ago

Press Release7 months agoU.S.-Africa Chamber of Commerce Appoints Robert Alexander of 360WiseMedia as Board Director

-

Business and Finance8 months ago

Business and Finance8 months ago360Wise Media and McDonald’s NY Tri-State Owner Operators Celebrate Success of “Faces of Black History” Campaign with Over 2 Million Event Visits

-

Ben Crump7 months ago

Ben Crump7 months agoAnother lawsuit accuses Google of bias against Black minority employees

-

Fitness7 months ago

Fitness7 months agoBlack sportswear brands for your 2024 fitness journey

-

Theater8 months ago

Theater8 months agoApplications open for the 2020-2021 Soul Producing National Black Theater residency – Black Theater Matters

-

Ben Crump8 months ago

Ben Crump8 months agoHenrietta Lacks’ family members reach an agreement after her cells undergo advanced medical tests