Viktor FarrAND private in the 1st Infantry Battalion, he was one of the first to land at Anzac Cove just before dawn on April 25, 1915.

© Commonwealth of Australia (National Archives of Australia) 2024, CC BY-NC-ND

In the chaos, Farr was lost. When the first roll call took place on April 29, he was nowhere to be found. His file was listed as “missing,” which sent every parent right into a blind panic.

It was not until January 1916 that it was determined that Farr had been killed in motion in Turkey between 25 and 29 April. He was 20 years old at the time of his death.

His mother, Mary Drummond, waited in agony for months for any news about her only child. Her initial respect for the authorities gave way to increasingly desperate and offended correspondence. She he wrote: :

Now Lord, I believe it’s your duty (…), when a mother gives up her son (…), when that son is injured, she must have some message.

In October she tried to seek help from her local MP, begging him discover if her son is alive.

However, it was not until 1921, six years after Farr was last seen alive, that the Army admitted that an exhaustive investigation had failed to locate his body. She he replied: :

I just wish you’d tell me, in the event you knew he was buried, my sadness would not be so great.

Farr’s name is carved on a panel on the street Lone Pine Memorial to the Missing in Gallipoli and beyond than 4900 his Australian companions, who also haven’t any known grave.

A heavy price

Nearly half of Australia’s eligible white male population volunteered and enlisted First Australian Imperial Force between 1914 and 1918.

Of the 416,000 who joined, over 330,000 people served abroad. Those over 60 thousand won’t ever come back. These are amongst the highest death tolls of any fighting country in the entire war.

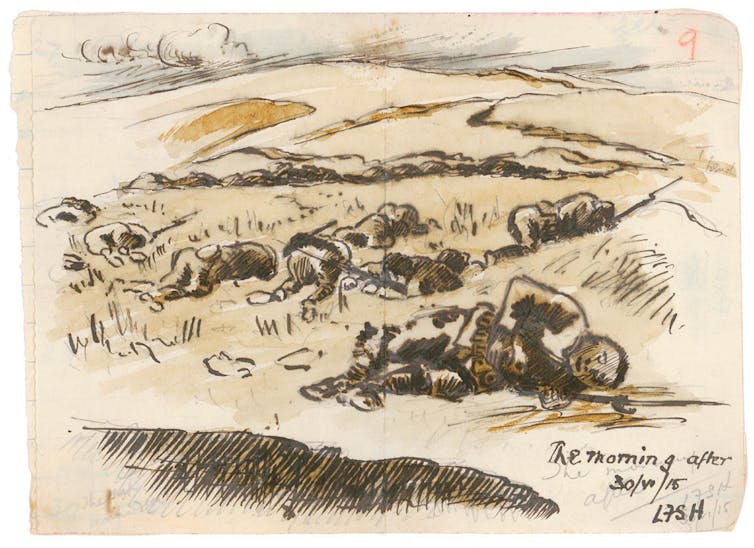

Leslie Hore/Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales

Over 80% the Australian soldiers were single, as was Farr; in some rural communities the rate was about 95%. Thus, the burden of mourning fell on the shoulders of aging parents.

The impact of wartime bereavement on aging parents was enormous. For some, sadness became the predominant theme for the rest of their days. For most of them, this memory haunted them until the post-war years, and for all of them the war became a key event of their lives, after which nothing was the same.

Some were sent to psychiatric hospitals

The physical health of many parents dropped quickly after they discovered their son had died. One example was Katherine Blair. She died unexpectedly at the age of 54 from heart failure on the first anniversary of his son’s death in France.

There is evidence that moms and dads behaved aggressively and contemplated suicide, causing disturbances of public orderand in the face of despair they turn to alcohol.

As I described in my doctoral thesis, many working-class moms and dads ended up in the wards of public mental hospitals similar to Callan Park in Sydney. Some stayed there for the rest of their lives.

Adam.JWC / Wikimedia Commons, CC BY

Psychiatric records I examined from several major psychiatric hospitals showed evidence of delusions, fantasies, and complete denial of his son’s death. Some lost multiple son.

Upper-class families avoided the stigma of public mental hospitals because they might afford visits to private doctors and nursing care at home.

Upper-class fathers specifically appointed themselves guardians of their son’s memory. They devoted enormous amounts of time, effort and funds to lobbying the Australian government to recognize their son’s services and to creating elaborate commemorative books and commemorative artifacts. Perhaps it was the so-called an indication of obsessive griefbut inaccessible to working class families.

How grief has changed

Death and injury during the war affected every part of the country, from cities to villages, from towns to stations.

The scale of the losses was as shocking because it was unprecedented, and it changed the situation permanently culture of mourning internships in Australia.

Funeral services and overt displays of mourning varied by class. Overall, nonetheless, the Australian experience of death in the nineteenth century was based on the traditions adopted in Victorian England – attendance at the deathbed, the funeral service, the gravestone and its inscription, and the physical act of visiting a grave to lay flowers or other memorials. for special occasions.

There was also a custom of wearing mourning black, and in the case of wealthier families, ornate funeral processions were organized through the streets with feathered horses to exhibit the social standing and piety of the deceased.

Australian ~mobs/Flickr

However, so as to mourn in the comfort of familiar rituals, two realities were needed – knowledge of how and where their loved one died and the presence of the body.

None of these were available to bereaved people in Australia during the Great War. These established, reliable patterns have been removed.

Instead, with so many individuals grieving, the idea of publicly describing their loss was seen as distasteful and vulgar.

Instead of an ostentatious public display, funerals became private affairs for family and shut friends.

Grief was endured and expressed in the privacy of one’s home, while publicly displaying dignified stoicism. The practice of wearing mourning black fell out of fashion.

estimated 4000-5000 war memorials were erected throughout the country. They became a point of interest in the community where people could honor their dead and remember their sacrifices, something we still see on Anzac Day.