Government spending on health is growing so fast that a decade ago then-Health Minister Peter Dutton called it “fractious“And”unbalanced“.

Health care spending increased by 44% in real terms within the ten years to 2021-2022. Real GDP increased by 26% over this era, so we’re spending increasing amounts on health as a proportion of GDP.

Until recently, we had no idea whether this extra spending was worthwhile – whether it made Australians healthier, and whether every dollar made Australians healthier over time.

In other words, we had no idea in regards to the productivity of the health care system. Statistical Office it doesn’t measure it in national accounts.

As with defense, we’ve got at all times only known how much we spent on health, without necessarily knowing what we were actually getting for the cash and whether our price for money was improving or not.

Productivity in healthcare has been a mystery until now

Piecemeal attempts to higher control the productivity of health care services have defined performance because the variety of medical or hospital services or pharmaceutical products delivered for every dollar spent. These trials showed only a slight increase in productivity.

The problem with these estimates, nevertheless, is that they don’t measure the necessary outcomes of upper health-related quality of life and longer life resulting from treatment.

Now, for the primary time, the Productivity Commission has attempted to measure what actually matters. And what did it give you? surprising.

The Commission found that between 2011–2012 and 2017–2018, while productivity growth out there sector across the economy grew by 0.7% per 12 months, the productivity of the health care sectors it examined increased by 3% per 12 months.

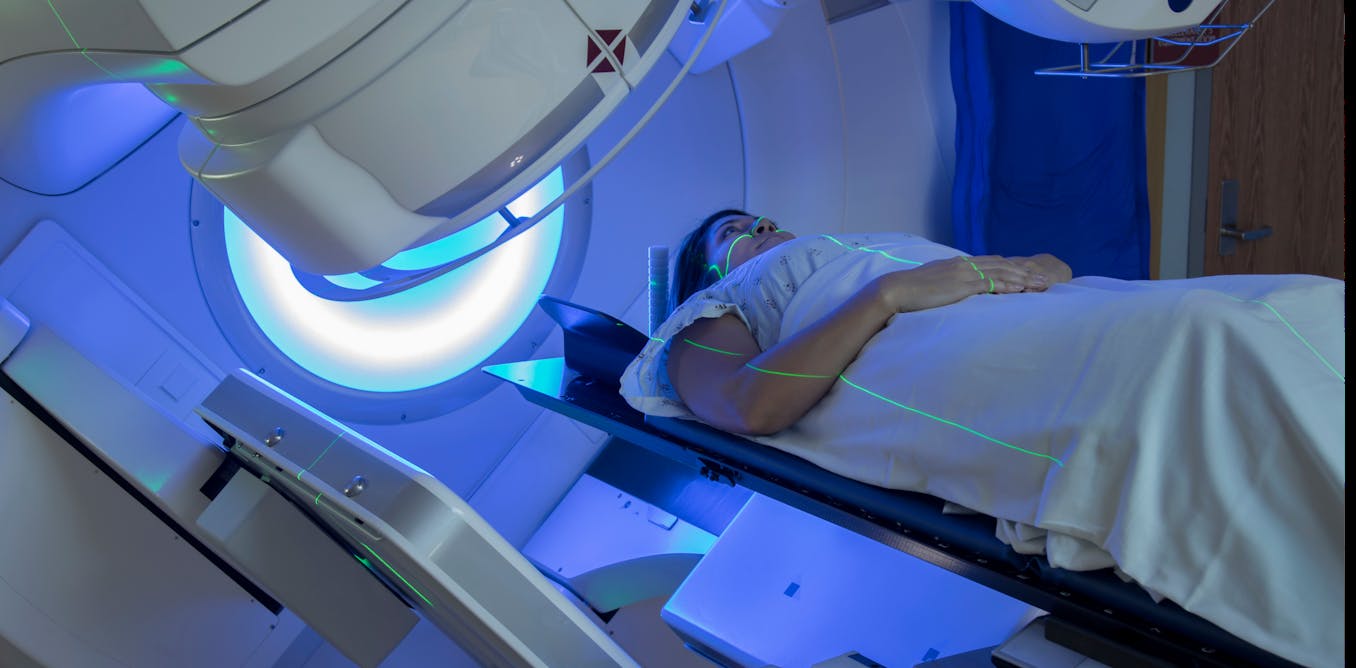

The sectors the Commission was capable of examine were those treating cancer, cardiovascular diseases and “blood, endocrine and kidney diseases”.

The Commission says its findings suggest:

(…) the extra spending within the parts of the health care sector we studied “was worth it” – it produced a net profit to society.

However, the finding of a mean increase of around 3% per 12 months hides clear differences in productivity growth by disease.

In the case of cancer treatment, productivity growth is about 9% per 12 months, which is much higher than productivity growth within the economy as an entire. However, when treating heart problems, productivity declines by roughly 4% per 12 months.

Cancer treatments work higher

The large improvement in cancer treatment productivity is not surprising. Survival rates for cancer patients have been steadily improving, from a five-year survival rate of 52% within the early Nineteen Nineties. 70% in 2014-2018.

This is an improvement more than large enough to offset the relatively high increase in actual cancer spending, 36%, over the period considered.

More surprising is the decline in productivity of cardiovascular treatment.

This is partly on account of a big decline in premature cardiovascular mortality rates 21% in the course of the study period was on account of aspects aside from medical expenses, including smoking reduction.

Other heart attacks could also be more difficult to treat

Moreover, the successes we’ve got had in stopping heart problems in recent a long time may make it more difficult to treat people that suffer from it.

Fewer people affected by heart attacks and strokes may mean that the remaining cases admitted to hospitals are more complex and more expensive to treat, reducing the apparent productivity of treatment.

It is also possible that there are data errors within the productivity estimates. It is likely that some cardiovascular treatments are cost-effective and others are usually not, causing the mix of various therapies to cut back overall productivity.

The Commission is right to call for more research and higher data to seek out out.

There are difficult decisions ahead of us

The commission examined only a few third of health treatments.

The remaining two-thirds are necessary diseases equivalent to mental illness, dementia, infectious diseases and musculoskeletal disorders.

The Commission has done some work mental illness. It found that outcomes would improve if resources were moved from hospital treatment to cost-effective treatment locally and enhancements in issues equivalent to insufficient income, employment, housing, social support and justice services.

As the Commission does more, it can even need to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions that prevent disease, in addition to those who treat it.

Productivity Commission

The commission’s findings are excellent news for the health care system because they indicate it is becoming more productive than previously expected.

However, differences in productivity between different sectors indicate room for further improvement.

Some improvements would require taking resources from underperforming treatments and transferring them to new, more cost-effective therapies. This is not going to be popular with providers of existing treatments.

Yet this is precisely what we are going to need if we’re to proceed to enhance health outcomes without increasing health care spending even more as a percentage of GDP.

It is not going to be easy, but the committee’s work is heading on this direction.