Surviving lung cancer in Aotearoa New Zealand may rely upon whether you’ve access to a GP, raising questions on equity in the country’s healthcare system.

Our latest research examines the outcomes of patients diagnosed with lung cancer by their family doctor compared with patients diagnosed with lung cancer in the emergency department (ED).

Analyzing 2,400 lung cancer cases in the Waikato between 2011 and 2021, we found that folks diagnosed with lung cancer after ED visits tended to have later stage disease and worse outcomes compared to people diagnosed after referral to a GP.

We also found that diagnosis after an ED visit was 27% higher for Māori than non-Māori and 22% higher for men than women.

These results raise necessary questions on health inequalities in New Zealand and highlight the necessity to ensure everyone has access to early cancer diagnosis.

Limited access to on a regular basis health care

Currently half of all general practices have closed their books to latest patients, leaving 290,000 patients unregistered and depending on emergency departments for healthcare.

As of 2019, roughly 80% of practices closed their books to latest patients sooner or later.

For people registered for an internship, waiting time for appointments are sometimes such that the one option is to go to the emergency room for help.

This is particularly true in rural areas, where the hospital may grow to be the default route to diagnosis.

Lung cancer is probably the most common explanation for cancer death in New Zealand – there are over 1,800 per 12 months. About 80% of individuals diagnosed with lung cancer have advanced disease and have a very poor likelihood of survival.

It can also be the cancer causing the biggest capital gap. The mortality rate for Māori individuals with lung cancer is three to 4 times higher than for people of European descent.

While much of this disparity is due to differences in smoking rates amongst ethnic groups, it also exists evidence delays in diagnosis and poorer access to surgery even have a major impact on survival.

Identification of lung cancer

Lung cancer often begins in the tissue lining the airways, and symptoms may initially be relatively minor – shortness of breath when exercising, a nasty cough, or sharp pains when respiration.

Patients with some of these symptoms will often go to their GP to see whether it is something that requires further investigation.

However, if someone cannot make an appointment or doesn’t consider the symptoms to be serious, they’re likely to delay taking motion.

Advanced symptoms of lung cancer include coughing up blood or lumps in the neck due to the lymphatic spread of the cancer. People with these disturbing symptoms often go to hospital for treatment.

Our study confirms previous findings that folks diagnosed in the emergency department include:

- more vulnerable to advanced disease

- A more aggressive variety of cancer is more common (so-called small cell carcinoma), I

- they’ve a much lower likelihood of survival.

The median survival for individuals who never presented to the ED was 13.6 months, while the median survival for individuals who had one ED visit was only three months.

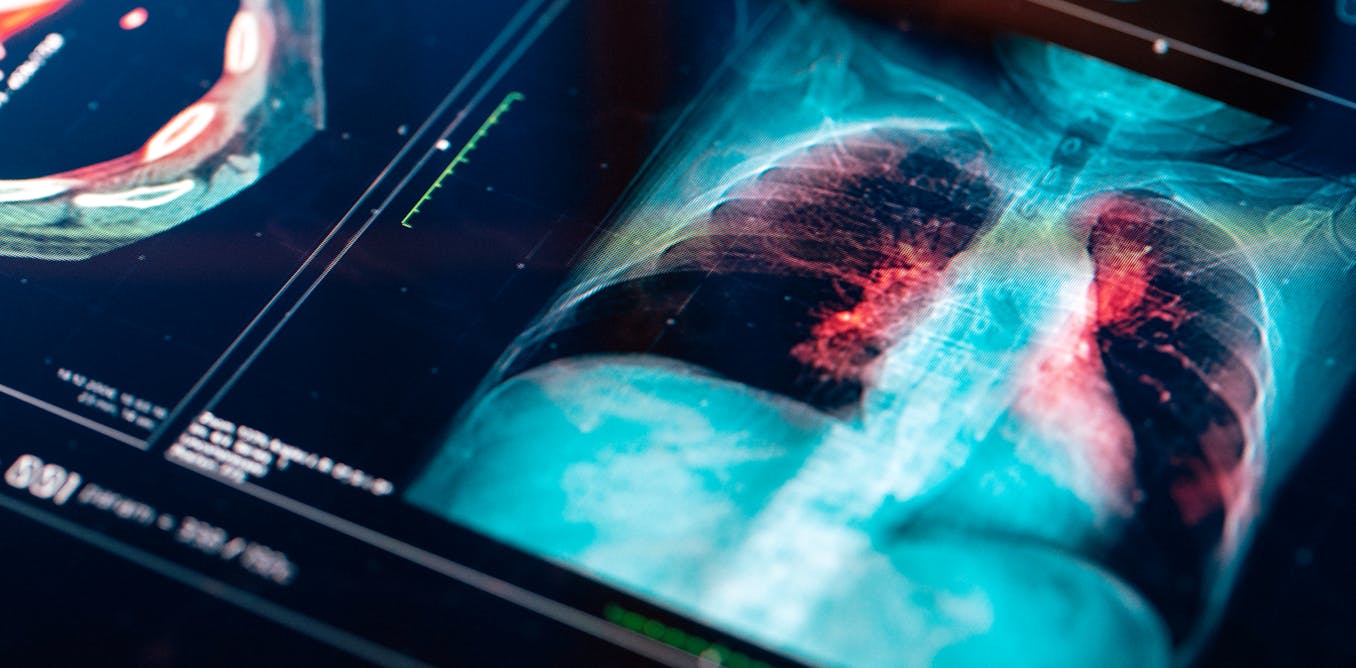

That said, there are some advantages to visiting the emergency department. These include seeing a doctor inside hours, quick access to X-rays and, in our major hospitals, access to the last word diagnostic tool for lung cancer – computed tomography (CT).

Our study found that 25% of cases presented to the emergency department two or more times in the 2 weeks before diagnosis. This was particularly true for people going to certainly one of the agricultural hospitals in the Waikato, where it was more likely that a second or third visit was required before a diagnosis could possibly be made.

Barriers to care

It is obvious that there are still several barriers to access to primary healthcare in New Zealand. This has led to an over-reliance on emergency departments to diagnose cancer, despite the lengthy process faster cancer treatment goals.

The situation is unlikely to improve. Access to primary care physicians is deteriorating, in part because increasing fees.

Māori and Pacific patients had lung cancer less likely than other ethnic groups who were enrolled in a primary care organization on the time of diagnosis. They were also less likely to visit their GP in the three months before diagnosis.

Making visiting your loved ones doctor easier

Increasing access to overall care is probably the most effective way to eliminate inequities in our lung cancer statistics.

Currently New Zealand only has 74 general practitioners per 100,000 inhabitants people compared to 110 in Australia.

It is obvious that we want to significantly increase the variety of general practitioners. This is a long-term project, however it have to be a strategic goal for the health sector.

In the meantime, we want to increase the provision of primary care by increasing patient subsidies and reducing the direct costs of doctor visits. At the identical time, we want to higher equip primary care physicians with access to diagnostic facilities, including in our rural hospitals.