Last month, a delegation led by Brendan Crabb, head of the Burnet Institute, a prestigious medical research institution, met with Anthony Albanese on the Prime Minister’s office in Parliament.

Its members, including Lidia Morawska of Queensland University of Technology, a world expert on air quality and health, also attacked ministers and staff, urging the federal government to lead a comprehensive policy on clean indoor air and for the problem to be placed on the national cabinet agenda.

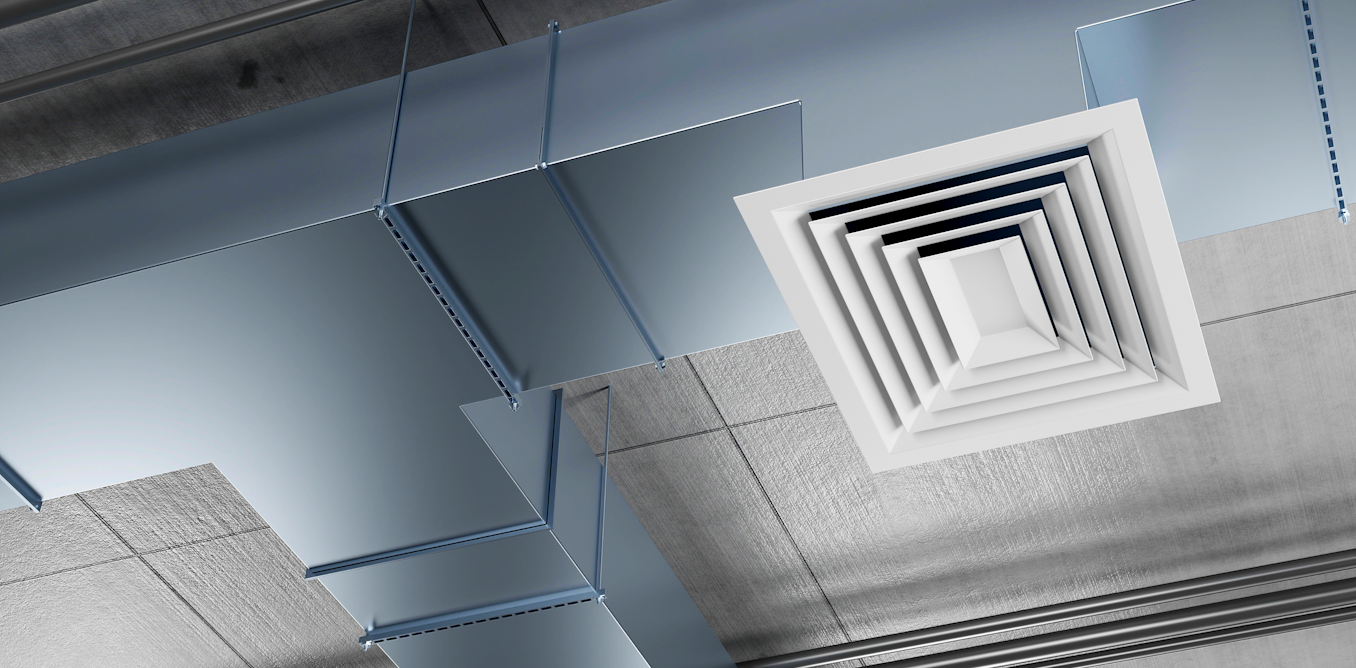

They identified to Albanese that indoor air is an exception in our otherwise comprehensive public health system. Despite people spending most of their time indoors, indoor air quality is basically unregulated, unlike standards that apply to things like food and water.

There are many health and economic reasons to be concerned about air quality, and one of the crucial essential is to reduce the spread of airborne diseases like COVID.

For lots of us, COVID has change into a foul memory, despite its enduring and mixed legacy. For example, if it weren’t for the pandemic, fewer people could be working from home now. More small businesses could be thriving in our CBDs. You could argue that fewer children could be trying to catch up on under-education.

Even though the media has largely lost interest in COVID-19 and individuals are relatively indifferent to it, the disease continues to take its toll.

There will likely be around 4,600 deaths attributed to COVID-19 in 2023, and in point of fact the number is probably going higher, on condition that Australia has had 8,400 “excess deaths” (defined as the variety of deaths exceeding the variety of expected deaths) this yr.

As of July this yr, 2,503 deaths have been recorded due to COVID-19.

In nursing homes, while COVID survival rates have improved significantly thanks to vaccinations and antiviral drugs, there are 117 energetic outbreaks as of September 19, with 59 latest cases up to now week. There have been 900 deaths this yr.

Long COVID has change into a significant issue, with a wide range of respiratory, cardiac, cognitive and immunological symptoms. It is estimated that there are between 200,000 and 900,000 people in Australia I currently have long COVID.

Albanian authorities are currently awaiting a commissioned report on their handling of the COVID pandemic.

The study checked out the Morrison government’s performance, but its scope didn’t include the states. This limits its usefulness, but there was politics involved, given Labor’s influential state governments.

Not that the state and territory leaders from those days are still alive (aside from Andrew Barr within the ACT). The faces that had change into so familiar from their day by day press conferences had vanished into oblivion: Dan Andrews in Victoria, Mark McGowan in Western Australia, Gladys Berejiklian in New South Wales, Annastacia Palaszczuk in Queensland.

COVID has had a wide range of effects on or damaging the reputations of leaders. McGowan, specifically, has reached stratospheric heights of recognition. Andrews has deeply divided people.

Overall, COVID has strengthened support for leaders and increased public trust in them and in the federal government. In times of uncertainty, the general public turned to established institutions and authorities. Trust has since declined again.

The experts found one another throughout the pandemic, but then found themselves in the midst of political arguments. In retrospect, a few of them were improper.

Marc McCormack/AAP

Overall, especially when it comes to mortality and the economy, Australia has weathered the crisis well. But in the event you look closer, the story is more complex, as documented by two leading economists, Steven Hamilton (based in Washington and affiliated with the Australian National University) and Richard Holden (of UNSW).

In their recent book Australia’s Pandemic Exceptionalism, the authors concluded that Australia had been largely successful in its (very costly) economic response, but that health outcomes were mixed.

While Australia quickly emerged from the blocks, closing the border and introducing other measures, it suffered a dramatic setback on two fronts: the Morrison government failed to order a wide selection of vaccines and failed to buy enough rapid antigen tests (RATs).

“The vaccine acquisition strategy was an irreversible disaster,” Hamilton and Holden write. It was not only “the biggest failure of the pandemic – it was probably the biggest public policy failure in Australian history.”

“We put all our vaccine eggs in two baskets,” each of which failed to various degrees. That was “a terrible risk. Pandemics are times of insurance, not gambling,” they write.

“And while our tax and statistics agencies mobilized to move much faster and more efficiently to meet the desperate needs of a government facing a once-in-a-century crisis, our medical regulatory complex repeatedly ignored international evidence and experience, and our political leaders deferred to their advice. And then the Prime Minister told us that when it comes to vaccinating Australians, ‘this is not a race.’”

The inability to order every vaccine that was expected meant that when there have been problems with production or delivery of vaccines that we were counting on or had already ordered, their rollout was delayed.

After that mistake, “to our bewilderment, we turned around and made the same mistakes all over again,” failing to obtain and freely distribute an enormous variety of RATs. In that failure, “our federal government demonstrated the same lack of foresight, the same thrifty but foolish attitude, that it has shown in the vaccine rollout.”

The authors blame Scott Morrison, then Health Minister Greg Hunt, then Chief Medical Officer Brendan Murphy, the Therapeutic Goods Agency (TGA) and the Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation (ATAGI) for health failures that prolonged the lockdown, cost lives and delayed the reopening.

In calling for higher preparation for the subsequent pandemic, Hamilton and Holden have an inventory of suggestions. They emphasize that we want to be certain that we’ve got the capability to manufacture an mRNA vaccine (which has made quite a variety of progress). We need to get the vaccine “right off the bat,” no matter cost. Massive quantities of RATs must be acquired as soon as they change into available, ready for immediate use.

The medical-regulatory complex needs to be completely overhauled. Australia also needs to proceed to spend money on its “economic infrastructure.” Economic strain has been made easier throughout the pandemic by the single-touch payroll system. “The first obvious candidate for improvement is the ability to report GST turnover in real time.”

Perhaps a comprehensive indoor clean air policy may very well be added to the list of infrastructure elements.

The government review may have its own recommendations. Crabb and his colleagues hope they are going to include attention to indoor air quality, the next suggestions from the Chief Scientist and the National Council for Science and Technology.

The delegation members say the Prime Minister listened to them rigorously.

Anna-Maria Arabia, chief executive of the Australian Academy of Science and a member of the delegation, says Albanese “understood that improving indoor air quality was a fundamental requirement for preparing for future pandemics and (he) was aware of the practical implications of having good indoor air quality systems, including the ability to keep schools and workplaces open and functional, reduce absenteeism and increase productivity”.

But beyond awareness, timely political motion is required. Pandemics don’t give many signals about their arrival.