Diabetes is a worldwide health problem. People with the disease produce little or no insulin, or have an ineffective response to insulin, causing their blood sugar levels to change into abnormally high.

Among the several types of diabetes, type 1 is commonest in children and adolescents – in 2019 about 1.5 million people under the age of 20 affected by the disease worldwide, and of the 16,300 deaths attributed to diabetes in people under 25 years of age, 73.7% of cases were attributable to type 1 diabetes.

Despite recent progress, treating this disease still poses a challenge to healthcare systems worldwide.

An enormous health problem for youngsters

Type 1 diabetes is (*30*)chronic autoimmune disease in which the immune system attacks and destroys the cells in the pancreas that produce insulin. To make up for the deficiency, patients should be given insulin via injections or delivery devices reminiscent of insulin pumps.

People with diabetes must also monitor their blood sugar levels, in addition to their nutrient intake (especially carbohydrates), physical activity, and other aspects that may change blood glucose levels.

Poor disease management raises blood sugar levels. Over time, this could affect or damage major organs in the body, including the heart, blood vessels, nerves, eyes, and kidneys.

It is subsequently crucial to grasp changes in the variety of young individuals with the disease, to find out its causes and supply medical examiners with data that can help discover new cases as early as possible.

The variety of cases has almost doubled

To provide much needed information, the occurrence was investigated – the percentage of new cases of the disease in a given time period relative to the population more likely to develop it – type 1 diabetes in 32 European countries between 1994 and 2021. To do that, we analysed a complete of 75 studies covering 219,331 people aged 0 to 14 years.

We found that the incidence of type 1 diabetes has increased significantly: from 11 cases per 100,000 years-person in 1994–2003 to roughly 21 cases per 100,000 person-years in 2013–2021.

Differences between countries

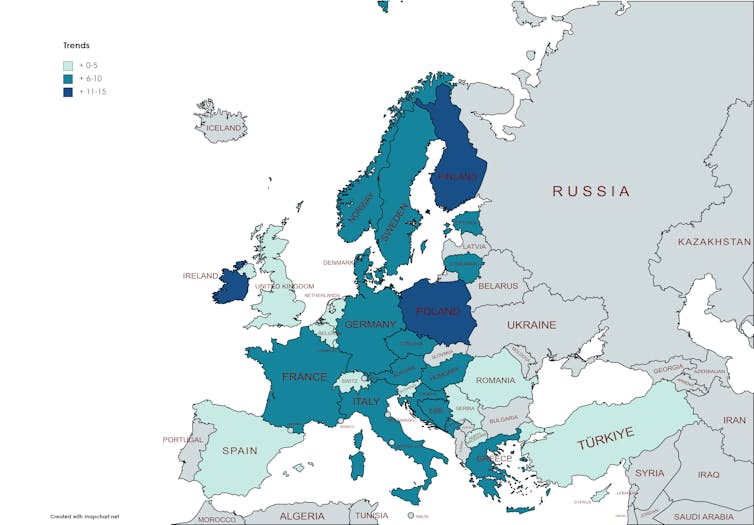

In addition, we identified significant differences between European regions. While there’s a transparent upward trend in most European countries – especially in Northern Europe reminiscent of Finland, Sweden and Norway – in some figures, including the UK and Spain, they seem to have stabilised.

In 2013–2021, the latest period studied, the lowest incidence rate was recorded in Romania and Turkey (11 and 12 cases per 100,000 person-years, respectively), and the highest in Finland and Ireland (56 and 33 cases).

In Spain, the increase was less steep, with 16 cases per 100,000 person-years reported between 1994 and 2003, increasing only barely to 17.5 between 2013 and 2022.

Across Europe, boys showed barely higher numbers than girls. We also observed that incidence rates increased with age, particularly in the 10-14 age group.

What is behind these rising numbers?

The origins of type 1 diabetes are still unknown, although some lines of research indicate that there’s a genetic predisposition. Other triggers have also been suggested, including: autoimmune processes, virusesand lifestyle or environmental aspects reminiscent of weight loss plan.

We also observed that higher per capita income or living in a rustic further north, reminiscent of Finland, Sweden or Norway, may affect the incidence of type 1 diabetes.

There are several possible explanations for this phenomenon, including the undeniable fact that northern countries receive less ultraviolet radiation (i.e. sunlight) – several studies found that exposure to ultraviolet radiation may protect against diabetes since it slows down the body’s immune response.

The effect of the pandemic

Another noteworthy fact is the increase in the variety of new cases of type 1 diabetes in children worldwide since the COVID-19 pandemic.

This could also be attributable to the impact of infection on the immunity of susceptible people or the limited ability of health systems to detect the problem early and keep it under control.

Further work is now needed on health policies that promote healthy lifestyles and control environmental risk aspects that underlie the immune problems related to this major public health challenge.