Sports

Fifty years after Hank Aaron’s 715th home run, his legacy remains in Gresham Park

ATLANTA — On the eve of the fiftieth anniversary of Henry “Hank” Aaron breaking Babe Ruth’s home run record, Gresham Park on Eastside Atlanta hosted an event inviting Black teenage baseball players on a visit to Chicago for an exhibition. The event, organized by the baseball association of former Atlanta Braves outfielder Marquis Grissom and Mentoring Viable Prospects, brings together dozens of young black baseball players from across Atlanta.

It’s in Gresham Park, where 50 years of Black history, Atlanta history and baseball history converge, where Aaron’s ball looks like it’s still going as much as the sky and everybody down there may be attempting to survive and play the sport they love.

As I pull as much as Gresham Park, a black kid who cannot be older than 10 or 11, wearing baseball shorts and cleats, runs across the car parking zone, a rag flapping in the wind behind him. It’s a picture you’ve got been led to consider is not possible: Little boys in Black Atlanta don’t care about baseball anymore, they’d reasonably spend their time on their phones or play basketball or football. And while which may be true for many individuals, it is not true for a child and his friends who try to get a spot at an exhibition game in Chicago in May.

I attempt to follow the child with my eyes to see where he’s running. I feel he’ll team up with a few of his teammates. Maybe he will consult with his mom on the sidelines. But I’m losing it because my eyes are actually on the batting cage. A black dad throws the ball to his son and offers him instructions with every swing.

Atlanta is a city uniquely positioned to have a good time its black heroes. Of course, to do that requires a singular combination of black political power and luck. But wherever you switch in town, you may see the names, likenesses or monuments of such black icons as civil rights activists Martin Luther King Jr., Ralph David Abernathy and John Lewis.

Aaron is one in every of those icons.

MLB via Getty Images

Aaron, a Southern kid born in Mobile, Alabama, who became a Negro League phenom and an MLB phenom all over the world from Boston to Milwaukee, got here to Atlanta with the Braves for the 1966 season. That season began a couple of months after the Voting Rights Act was signed into law 1965 A couple of months into the season in June, black nationalist Stokely Carmichael stood before a crowd in Greenwood, Mississippi and called for Black Power.

In some ways, Aaron would represent the subsequent phase of Black empowerment, where Black people had the chance to enter newly desegregated spaces and show that they might dominate. One where white people could attempt to discredit their skills, but they only couldn’t because a black kid from Alabama was hitting 30 home runs a season. And he broke baseball’s most beloved record in the face of racism and death threats, all in a city that had change into a black mecca.

In the early 2000s, the Gresham Park area of Atlanta was 95% black. It was the heartbeat of town, but at the identical time a neglected space. Still, the park was known for showcasing town’s best black baseball players, who went on to play at historically black universities, other colleges, and even in the professionals. Recent players who’ve passed through Gresham Park include Oakland A’s right fielder Lawrence Butler, Tampa Bay Rays pitcher Taj Bradley and Braves center fielder Michael Harris.

In 2021, the Braves renovated the park, repairing three diamonds. When I got to the park, I saw something I didn’t expect: two of the parks were hosting games played by white teams with white audiences. This can be Atlanta, where gentrification is rampant and places that look latest suddenly change into home to white people. By the way in which, the Gresham Park area is currently only 72% black.

Across from these games was an unrestored diamond that looked like old Gresham Park. This is where local kids are only beginning to learn the game. They are as much as 8 years old, wear T-shirts and sweatpants, catch their first ground balls and throw them somewhere near first base. They do that when the sound of aluminum bats hitting baseballs echoes across the polished fields where white kids play.

“I don’t know why our kids aren’t in these fields,” Jared Fowler said. He’s one in every of the Gresham kids’ coaches, and his son can be determining how you can play the bottom ball. He coaches because his dad introduced him to baseball at a young age and he desires to pass it on. “But this is what has been happening in this area for some time.”

Focus on sports via Getty Images

Fowler says kids change into interested in baseball at a really early age, but as they invest in other sports and hobbies, interest wanes. It’s a preferred story, but it surely’s undermined by what’s happening on the pitch behind the park. This is one other refinished diamond with the number 44, Aaron’s number, on the fence. It is on this diamond that black boys jump around, initially throwing rockets into outstretched arms, and batting practice turns right into a series of bombs falling off the back fence. from where perhaps sooner or later the subsequent great Hammerin’ will come.

He looks at Grissom’s brother, Antonio, who currently coaches the Morehouse College baseball team and helps scout players. Next to him is Greg Goodwin, a former Dodgers scout whose Viable Prospects Mentoring program can be undergoing a trial. About half of the children in these programs go to varsity to play baseball.

“We make sure we tell them about Aaron,” Goodwin said. “We make sure they know whose shoulders we are standing on.”

As we talk, one other man walks up, making fun of Morehouse along the way in which. He is older. Ralph Gullatt. He was the coach of Clark’s Atlanta baseball team. He grew up playing at Gresham Park, playing in the 12-year-old league in 1974.

So you were alive when Aaron broke the record?

Gullatt smiles.

“Oh, I was at the game.” His eyes never leave the diamond and watch the kids. He himself is as excited as a baby. Like he was watching Aaron break the record again. “My friend’s mother worked in concessions and got us a ticket. I happened to be there. I remember those white boys running at him. We didn’t know what was going to happen. “Amazing night.”

Gullatt goes back to talking nonsense. There are more men in the world who talk concerning the high schools that ruled the world. The best players to come back from Gresham. There are more white kids than before. They’re talking about baseball. But they’re talking about Atlanta. They discuss Atlanta, which owes a lot to Aaron. The Atlanta that embraced him, held him, and idolized him, despite the fact that much of the country – and parts of Atlanta itself – wanted him gone.

But Aaron and his legacy won’t fade away until there’s somewhat black kid in Gresham Park running to the baseball diamond to catch ground balls with a rag catching the air beneath it.

Sports

Minnesota Timberwolves Guardian Mike Conley “Having a ball” in search of the first NBA finals

San Francisco-Minnesota Timberwolves Guardian Mike Conley Jr. He danced after his training before playing on the Chase Center floor as Spun D-Sharp Golden State Warriors, “Life is Good”. After the end of the song, the 37-year-old tried to summarize.

After leaving the first attempt, Conley threw a second before he went to satisfaction to the cloakroom.

“I did it essentially throughout the season,” Conley said on May 12 to scape about his pregame dunk ritual. “They were like:” You cannot immerse. ” I told them, “I’m almost sure I can.” My coaches and teammates told me that I was going to be 38 years old. “

Conley hopes that he’ll soon win flowers as one of the oldest NBA masters, but now his Timberwolves are set off to the finals of the Western conference for the second 12 months in a row. The 18-year-old NBA veteran never played in the NBA finals. Since joining the NBA in 1989, Timberwolves has also never played in the NBA finals, losing in the finals of the Western Conference in 2004 and 2024.

Standing on the road to Minnesota, which appeared in its first finale, is Oklahoma City Thunder, Semen No. 1 of the Western Conference, which on average 24 years. Thunder host The Timberwolves tonight in the game 1 (ESPN, 20:30 et)

“Simply excited about the challenge of us,” said Conley. “We can compete with one of the best teams in the league to reach the NBA finals. We worked hard and focused. It should be a great series.”

For the aging Conley, he hopes that his third time, when a shot at the NBA finale, is a charm.

In 2013, 26-year-old Conley first appeared in the finals of the Western conference, but his Memphis Grizzlys was swept through San Antonio Spurs. At the age of 36, Conley and Timberwolves lost in five matches with Dallas Mavericks in the finals of the Western conference in 2024.

After the series, he wondered if it was his last likelihood to get to the NBA finals.

“I was really shocked because I thought it was a special year,” said Conley about losing in the finals of the Western conference last 12 months. “I thought it would make sense and we will all do it. My first thought was:” How long will it take us back here? Will it happen next 12 months. Will or not it’s one other 12 months? I do not know. Will or not it’s the last likelihood I’ll get? “

“All these thoughts were influenced. But this made me go in the summer, hoping that we would be able to do it again this season and have a chance.”

Noah Graham/Nbae via Getty Images

Conley was chosen with the fourth alternative at the NBA Draft in 2007 by Grizzlies. The only players in the NBA still remaining from this draft are Conley, the striker Phoenix Suns Kevin Durant, Boston Celtics Center/Forward al Horford and Houston Rockets Jeff Green. Horford won his first NBA title at the age of 37 from Celtics last season.

Conley was born on October 11, 1987 in Indianapolis. He is now the tenth of the oldest player in the NBA with Los Angeles Lakers striker Lebron James the oldest at the age of 40. New York Knicks, PJ Tucker, just over 4 months younger than James, is the oldest player remaining in the playoffs at the age of 40. James Johnson James Johnson is 38 years old.

“It’s terrifying, but also an honor,” said Conley. “I don’t feel that I’m so old, but I’m so old. I have to be fine with it and look in the mirror and say:” Man, we’re still doing it. ” “

Conley performed 76 performances in the season in the 2023-24 season, most frequently from 2012-13, and played in 15 Playoff matches. The essential coach of Timberwolves, Chris Finch, said he wasn’t planning to play Conley in so many matches this season in the hope of his behavior. Conley also got here in this season with a everlasting injury of the left wrist, which hinders his ability to address basketball or golf playing out of season. He scored a mean of 8.2 points and 4.5 assists in 71 matches of the regular season this season, playing a 24.7 minutes per match.

“One of the most difficult injuries was my wrist for me,” said Conley. “I needed to be in the forged for about two months of last summer. And at the moment I could not shoot the ball, touch the ball. Nothing. It isn’t like me. Usually I work and do all the pieces I can. So after I enter a training camp, I had no strength (in the wrist). It was poor (it was still pain and I attempted to work for some things.

“I hesitated before doing things and being myself. It was a battle (season). This is something that I slowly ended with. I hope it will be even better next season.”

Conley has the purpose of the game in 20 seasons of NBA. The next season can be his nineteenth and last 12 months of the contract with Minnesota for $ 10.7 million. Based on how Conley takes care of his body, he appears to be ready to attain his goal.

Departing from Indianapolis, he began to be more severe and more routine with a food regimen and training scheme in 2018 after surgery ending the season on the left heel after trying various options for the treatment of the side heel and Achilles. Conley felt his body breaks down, and said he needed to make a change to proceed fidgeting with less pain.

“I stopped eating red meat about eight years ago,” said Conley. “I did the work of blood, and my body was in some things, and fewer of some things. And beef was one of them. Something I do every single day, I get up around 7:30 (in the morning). I won’t eat until drinking water after 11 am. It’s almost like a quick.

“I try to extend it until I end up with treatment and exercise. I try to eat a meal. Good work, cleansing the intestine and stomach. You must heal yourself from the inside at my age. Cut off the inflammation that cause pain and slow down you at the age of 35, 36, 37 years.”

It is claimed that James spends $ 1 million on his body which he rejectedto maintain your health. While Conley doesn’t invest $ 1 million, he says that he’s investing financially in health and longevity. He said that he’s in a cold bathtub twice a day, and likewise performs a sauna of red light and a pool every single day, in addition to red light therapy, cryotherapy, STEM units (which incorporates their wearing while sleeping if obligatory) and lies in Softball to free pain from sore areas.

“I don’t have as much money as he,” said Conley about James. “But I also put a lot of money into my body. My diet is a big deal. My recovery is a big deal. From time to time I think Lebron:” I’m attempting to do what you do. ” Whatever it is, I need all this help. “

David Sherman/Nbae via Getty Images

Perhaps the most difficult part of being one of the oldest NBA players for Conley is what’s missing at home.

Conley and his wife Mary have three sons: Myles, Noah and Eli. Conley left Noah’s birthday on May 12, because Timberwolves were on the way in San Francisco in Play -ffach. He left Mother’s Day, and likewise Timberwolves defeated Warriors 117-110 in the match 4 of their second round in San Francisco the next day.

“I missed my son’s seventh birthday, Noah James Conley,” said Mike Conley. “He is a family speaker. A little bit joker. Just a shiny, supermart kid. He is my twin, the one who looks like me the most. He still wants me to hug him.

“But my wife did a great job, making him feel enthusiastic about himself. He had his little friends with a birthday celebration. … I used to be sex after they sang all the best and his friends arrived. Double Whammy.

There are 11 players on Timberwolves who’re lower than 25 years old, including 20-year-old debutant Rob Dillingham. Conley shares the outline with the 23-year-old NBA Guardian All-Star Anthony Edwards. But after 18 seasons of the game with mainly younger collaborators, Conley says that he still has love and fervour for taking part in.

“I have a ball, brother, to be honest,” said Conley. “I tell the boys all the time:” If you see the day after I don’t smile and haven’t got fun here and do not love, tell me to take a look at. Tell me to go home. ” This is one of the reasons I’m here.

“You don’t get it anywhere else in your life, especially my age. You can’t really take it for granted.”

Sports

WNBA testing racial insults by fans performed in Angel Reese while playing Indiana, AP Source

WNBA examines racial comments addressed to Angel Reese by fans during Chicago Sky’s Loss from Caitlin Clark and fever In Indiana on Saturday, based on a one who knows the situation.

The person talked to the Associated Press on Sunday, provided that the league didn’t publicly discover the subject of mockery or allegations.

“WNBA definitely condemns racism, hatred and discrimination in all forms – they do not take place in our league or in society,” said the league in an announcement. “We are aware of the allegations and we look at this case.”

Reese, which is black, and Clark, which is white, met for the seventh time in his time Ongoing competition-and very reproduced. Clark was appointed Rookie of the Year last season, and Reese took second place in voting.

The union of WNBA players published an announcement shortly after the League comment on this matter.

“WNBPA is aware of reports of hateful comments on yesterday’s game in Indianapolis and supports the current investigation of WNBA in this matter. Such behavior is unacceptable in our sport”, statement. “According to WNBA’s policy,” No Space for Hate “, we trust the league that they will examine and have taken quick, appropriate actions to ensure a safe and friendly environment for everyone.”

The president and general director of Sky, Adam Fox, later said on Sunday in an announcement that the organization accepts the investigation of the league.

“We will do everything in our power to protect Chicago Sky players and we encourage the league to continue taking sensible steps to create a safe environment for all WNBA players,” he said.

Heaven and fever will play 4 times in the regular season.

“We are aware of the accusations of fans inappropriate behavior during yesterday’s game and we work closely with WNBA to end their investigation,” said the fever in an announcement. “We stand in our commitment to ensure a safe environment to all WNBA players.”

Reese had 12 points and 17 rebounds in 93-58 losses with fever. Heaven and Clark took the incident on the pitch, and 4:38 remained in the third quarter. It began with Reese organizing the offensive reflection, and Clark hit Reese’s shoulder hard enough to calm down the ball and lightweight Reese to the ground.

When Reese got up She tried to confront Clark In front of the Indiana Center, Aliyah Boston entered between the players. Clark’s third personal foul was improved to the gross 1, while Boston and Reese drew technical fouls after reviewing the repetition of the referees.

Both players left the sport after the match.

This season, the league has launched a “No Space for Hate”, a multidimensional platform designed to combat hatred and promote respect in all WNBA spaces each online and in arenas.

The league focuses on 4 areas: improved technological functions to detect hateful online comments; Increased pressure on the safety measures of the team, arena and the league; strengthening mental health resources; and adaptation to hate.

This shall be the primary league test.

“It’s nice words, but we have to see actions,” said Aces A’ja Wilson on Friday after training. “I hope that people can take actions and understand that it is bigger than basketball. We are real people for this. Every shoe we wear, every T -shirt we have, we are people. People must respect it. I hope that they pay attention and listen to words.”

(Tagstotranslate) Angel Reese

Sports

Antonio Brown detained by the police in Miami after the arrows fired before the boxing event of Adina Rossa

The police in Miami stopped Antonio Brown to shots fired before the boxing event displayed via the Internet Streamer Adin Ross.

The incident took place at the starting of May 17, when Miami officers reacted to a notification from the shot detection system. Film material published on social media also showed that Brown is fighting many individuals outside the event. Observers recording the incident showed that Brown is supposedly falling and later digging a security officer during the test.

According to the former NFL star allegedly kept Black pistol while racing one other person. The shots diverged outside the camera, which led to the arrival of the police.

After the police questioned Brown and several other other individuals with potential commitment to the shooting, Brown divided the details of the social media sample. Brown appeared in Ross “Kick Livestream to blame his involvement in the fight for” cte “like Reported by . CTE, regressive brain disease formally often known as a chronic traumatic encephalopathy, stays related to contact sport akin to football.

“I got a cte, I pulled out the blackout,” he said on the stream. “I ended, Adin … I don’t know what happened.”

However, in the next post Brown claimed that many individuals jumped him, attempting to steal his jewelry.

As for the boxing event that took place last night. Many people jumped me who tried to steal my jewelry and cause me physical damage. Unlike some movies circulating, the police temporarily stopped me until they received my story, after which they didn’t publish me. …

– AB (@AB84) May 17, 2025

“As for the boxing event that happened last night,” he began in his position that “many people who tried to steal my jewelry and do physical damage to me.”

He also shared how he plans to take legal actions, and video virus on social media is a false narrative about what happened.

He added: “Contrary to some of the films, the police temporarily stopped me until they received my story, and then I did not release me. I returned home tonight and was arrested. I will talk to my legal advisor and lawyers about those who jumped on people who jumped in.”

A spokesman for the Police Department in Miami, officer Kiara Delva, confirmed that law enforcement agencies had not arrested at the scene. They also didn’t report injuries in their statement. Despite the reports about the lack of arrest, other circulating movies allegedly showed Brown in handcuffs.

Although his skilled sports profession suddenly ended in 2019, Brown remained a controversial figure from the field because of insolence and legal issues.

The investigation of shots stays. The police didn’t call every other suspects involved in the fight.

)

-

Press Release1 year ago

Press Release1 year agoU.S.-Africa Chamber of Commerce Appoints Robert Alexander of 360WiseMedia as Board Director

-

Press Release1 year ago

Press Release1 year agoCEO of 360WiSE Launches Mentorship Program in Overtown Miami FL

-

Business and Finance12 months ago

Business and Finance12 months agoThe Importance of Owning Your Distribution Media Platform

-

Business and Finance1 year ago

Business and Finance1 year ago360Wise Media and McDonald’s NY Tri-State Owner Operators Celebrate Success of “Faces of Black History” Campaign with Over 2 Million Event Visits

-

Ben Crump1 year ago

Ben Crump1 year agoAnother lawsuit accuses Google of bias against Black minority employees

-

Theater1 year ago

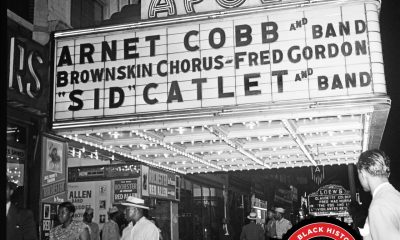

Theater1 year agoTelling the story of the Apollo Theater

-

Ben Crump1 year ago

Ben Crump1 year agoHenrietta Lacks’ family members reach an agreement after her cells undergo advanced medical tests

-

Ben Crump1 year ago

Ben Crump1 year agoThe families of George Floyd and Daunte Wright hold an emotional press conference in Minneapolis

-

Theater1 year ago

Theater1 year agoApplications open for the 2020-2021 Soul Producing National Black Theater residency – Black Theater Matters

-

Theater12 months ago

Theater12 months agoCultural icon Apollo Theater sets new goals on the occasion of its 85th anniversary