What does Indian and Pakistani press archives, government documentation and memories can tell us in regards to the Middle East of the Twenties and the thirtieth century, when the Empire of Great Britain was within the years of dusk? What he did dissolution Ottoman Empire, Movement to Egyptian independenceIs the crisis within the British mandate of Palestine related to the choice to divide India?

Like Muhammad Ali Jinnah, he moved from being a secular young man terrified Indian interference in Ottoman caliphate crisis To the moving spirit of demand on Pakistan – a latest Islamic nation that, he claimed, would have the ability to defend Muslims abroad?

These are types of questions that didn’t surprise me at night. The result of this insomnia is My latest bookEast of Empire: Egypt, India and the world between the wars.

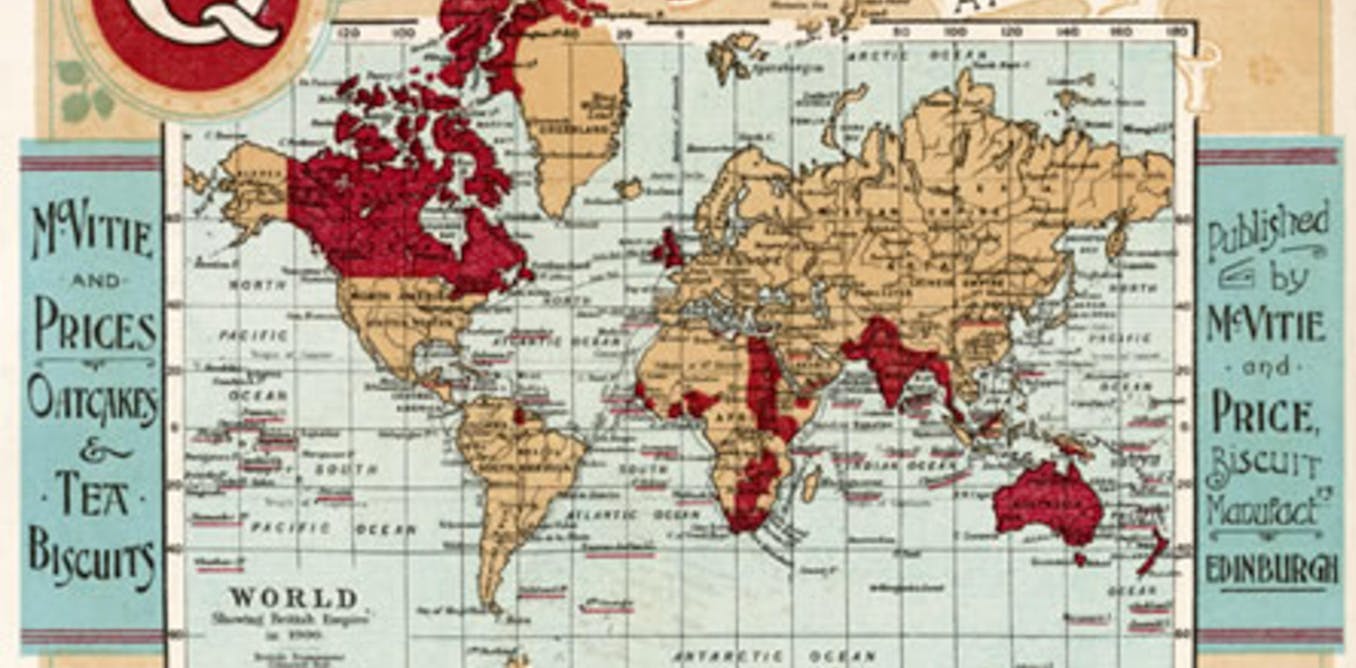

I give attention to a quarter of a century, which immediately preceded the tip of the Empire in India-Pakistan and Palestine-Israel. Both countries were divided into ethnic lines – the primary by the British, and the second by the UN – causing catastrophic bloodshed and forced displacement of thousands and thousands.

These partitions took place only six months in 1947–1948. They remain in the middle of terrifying state violence on each continents, not to say the intergenerational trauma and the wounded historical debate.

For most of the period, my book deals with, from 1919 to the mid -Thirties, the division of territory between religious or ethnic blocks could be difficult for most individuals within the Middle East and South Asia. There were no obvious boundaries that could possibly be drawn between local communities. Especially in cities and towns, neighbors of various ethnic groups and denominations lived on the cheek.

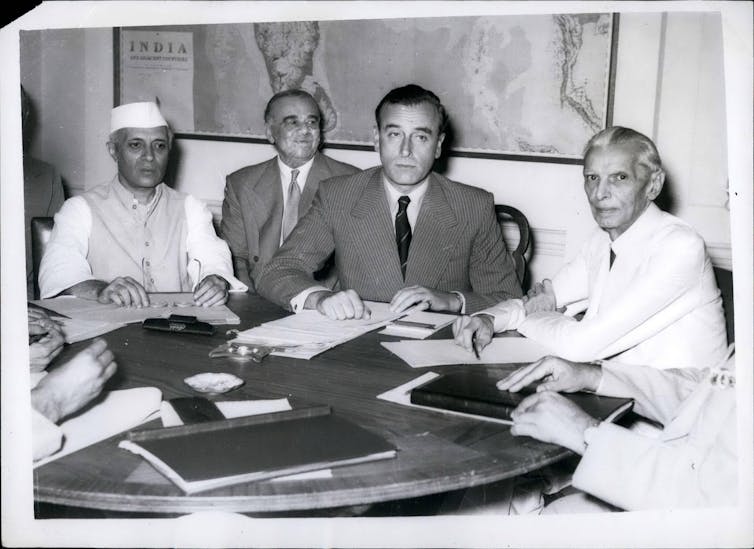

Keystone Press / Alamy

In fact, at that time, between the First and Second World War, the Egyptians and Indians considered their movements to self -determination as joint divisions.

Artists, politicians, activists and intellectuals described a dense and flexible network of mutual connections – some spiritual or language, other cultural and geopolitical – which together created something that known as, Orient or “East”. It was said that it exceeds every kind of barriers, depending on who you asked – faith, language, ethnic origin, nation, gender and class, to begin with.

Many historians writing about this era raised this “east” to closer control – only to postpone it quickly. They claim that it is simply too vague, amorphous and internally contradictory to be very useful as an analytical category. They usually are not flawed. In the Twenties and the Forties there have been many (maybe even countless) visions of the East in circulation.

There was an east of orientalists – a stranger, exotic and “different”. There was an anti -colonial east, geography of allies within the fight against foreign dominance. Then there was a spiritual east, often contrasting with a materialist West. There was an Islamic East, a region inhabited largely (though never exclusively) by Muslims. There was also a cosmopolitan east, a wealthy gobelin of cultures related to trade and exchange of ideas. Finally, there was a strategic east, a geopolitical block or a bastion that can counteract other constellations of power.

It is vital to emphasise that none of these concepts has been mutually exclusive. Instead, supporters of the eastern part often combined several “types of eastern ideas in a personal hybrid.

AP / Alamy

So, in his memory, Sultan Mahomed Shah, Aga Khan III, restored his long -term dream in regards to the Eastern Bloc of Muslim nations, serving each as a moral compass for the world and healthy control of the facility of Europe and the United States.

For the Egyptian feminist Huda ShaaraviThe east was undeniably anti -colonial. On the pages of his magazine L’EgePtienne was often ancient and exotic – but in addition, most significantly, the stage at which women from many cultural, ethnic and religious circles together create a future in their very own image.

Considering the stunning range of potential EASTS, they might never call the dorms a coherent ideology. But this didn’t prevent that that is a highly visible feature of each political debate and activities in Egypt, India and a wider Arab-Asian region throughout the interwar period.

Starting from the Twenties and deep within the Thirties, various eastern visions flowed and even with one another because the headlines modified, alliances have evolved and priorities moved. However, in the beginning of the war in Europe in 1939, the rates of these ideological differences began to grow.

Stanford University Press

Subscribed by the inexorable pressure of war, many Eastern threads began to spray, paying more smooth and open possibilities that enlivened the previous many years.

Post -war ideologies with sharper edges, hardened national borders and – after years of cataclysmic violence – a small faith in pacifist and humanistic ideals of the past era appeared of their Stead. This almost chemical transformation is a background on which the voices confirmed the partitions of India and Palestine in 1947.

Here, due to this fact, the story told within the east Empire: just like the visions of the transnational, liquid and unconform Eastern, shaped the interwar policy of India and Egypt, and why these visions gave option to a more rigid place, warming nationalism at the tip of World War II.

The book returns to a similar chapter within the creation of anti -colonism and the tip of the British Empire within the Middle East and South Asia. And explains the conditions during which these daring and optimistic visions have collapsed – releasing the stream of violence, which we’ve got not yet lost, almost 80 years later.