Perhaps you saw them in town or in news. Bumper stickers He gave Teslas to anyone who looks: “I bought it before we learned that Elon was crazy.”

It may be assumed that it’s there to forestall someone from taking a automotive or an try and relieve potential hostility in a hyper-political landscape. But although this will signal disapproval for similar considering passers -by, the sticker is unlikely to discourage someone who’s already going to commit against the law (which is the important thing).

What he offers is a type of symbolic insurance. You can call it a approach to explain identity in a hostile political environment.

An equal apology, protest and cultural time marker, the message can say more in nine words than a full -fledged. But it isn’t just about the automotive. It can be about values, identity management and evolving consumption policy.

Signal for others

In their core, automotive bumpers stickers act as a vehicle (literally and metaphorically) when it comes to identity projection. They are symbols of what psychologists call “Cheap identity displays”, used to display who we’re, or perhaps more precisely how we wish to be seen.

Buying Tesla could once signal innovations, environmental awareness or social progressivism. But the increasingly polarizing public behavior of Muska and political commentary They modified the cultural importance of the brand.

It creates a sense cognitive dissonance For those consumers whose values are not any longer consistent with what the brand owner now represents. Enter the bumper sticker.

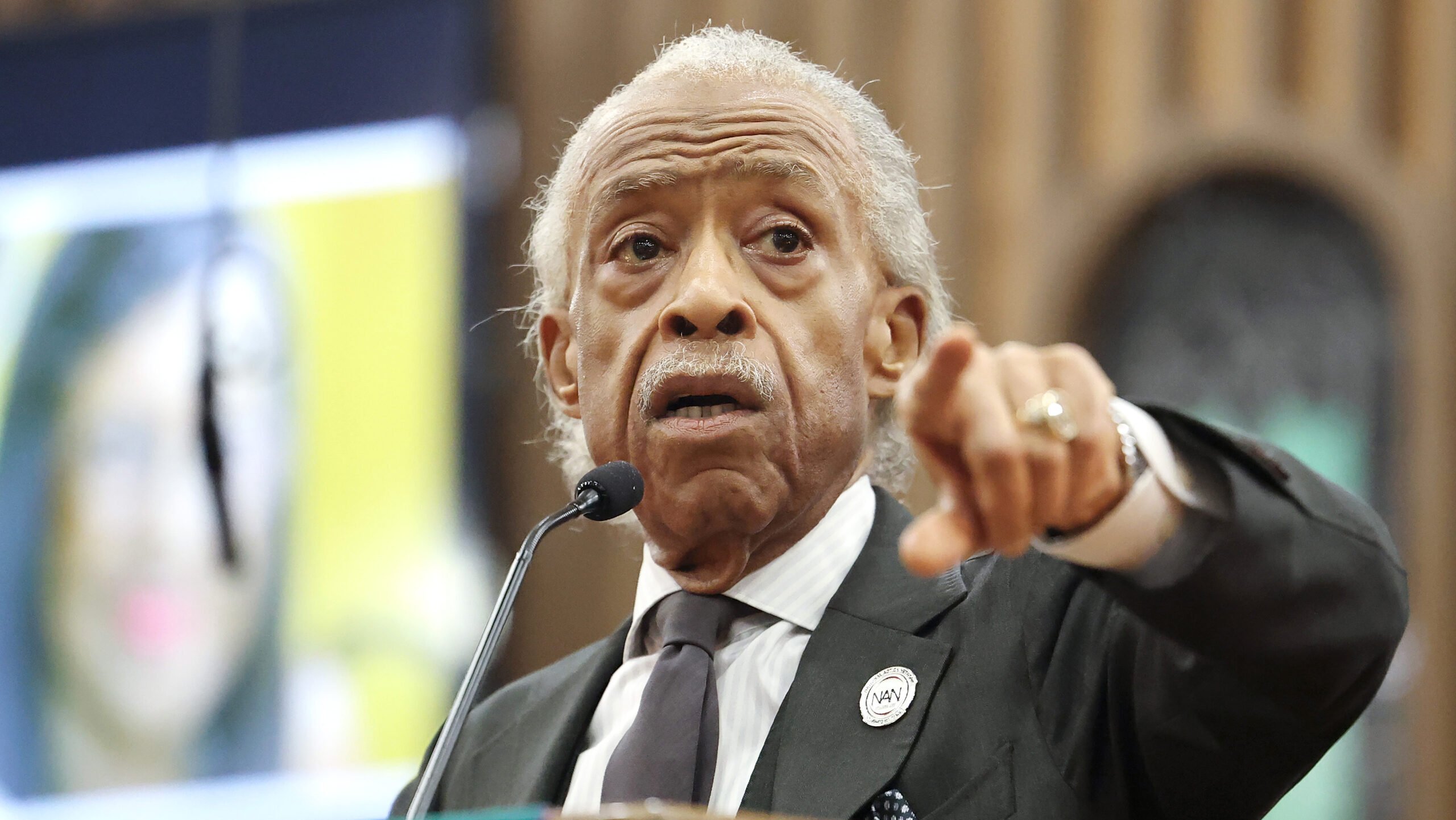

Shutterstock

In an increasingly fragmented society, through which individuals are completely happy to face out, even a sticker is usually a subtle form of ethical positioning. But above all, it’s a approach to signal groups that a very powerful for us “please like me”.

The theory of social identity suggests that folks derive a part of their concept of themselves from the perceived membership in social groups. Bumper stickers make these group connections visible, protruding values, ideologies, belonging and even contradictory attitudes towards the skin world.

My tiny, disappearing Richmond Tigers sticker on my automotive will not be performative in the identical way as a daring political slogan may be. But it still signals the shape of identity and belonging.

Shutterstock

North Face Jacket

Bumper stickers act as a “peacock” form. It is analogous to wearing branded clothes, equivalent to the North Face jacket during Covid, which made it look more accessible than in a proper suit. Or even like a biography curator at LinkedIn. It is a behavioral strategy through which people convey their qualities to others no words.

In marketing, it’s closely related to theory visible consumptionwhich can include symbolic consumption through which we buy and display products not just for utility, but additionally for what they Tell us about us.

Bumper stickers are a literal version of this. They are symbolic, declarative and public. These are the low, high credibility of the communicators of the belonging of a bunch, virtue, humor, riot or indignation.

It is about informing or convincing, but their actual impact is more complicated.

Marketing class 101

In preliminary marketing classes, taught at almost every university, consciousness is usually presented as the primary stage Effect hierarchy model. The model suggests that customers’ operation goes from consciousness to knowledge, preferences, preferences, beliefs and eventually purchase.

Shutterstock

But in practice this progress is way more complicated. Bumper stickers can generate consciousness, but little evidence affects behavior – especially in insulation.

This is especially essential in such areas because the promotion of tourism. For example, unofficial, but still a provocative tourist slogan Advertising campaign “Cu in NT” It may cause conversation and recognition, but recognition doesn’t mean conversion.

Despite the hope of hundreds of thousands of dollars spent on slogans and slogaty, consciousness is necessary, but insufficient for behavioral change.

Most marketing efforts should not said because people should not aware of the brand, but because they don’t have any reason, possibilities or tendency to act – that’s, buying a product or change.

The culture has shredded

Contemporary consumer culture is increasingly tribal and crushed. Social media algorithms strengthen the Echo chambers, while physical signals equivalent to automotive stickers and even political signs of Korflute signal belonging and limits within the group and group.

As a result, bumper stickers probably strengthen the identity of already converted, but it surely is unlikely to persuade people from outside the tribe.

Visible preferences can, nonetheless, function a type of abbreviations for identity, especially after they are consistent with the symbols and language of the group. Although their direct impact on behavior is restricted, these signals, repeated and reinforced within the premature community, can shape and move social norms over time.

Ultimately, bumper stickers rarely change behavior. But they do something more subtle. They allow people to precise, perform and ensure identity. They act as signals for other, tribe markers, values, humor or riot. They help us tell who I’m, or perhaps I’m not like that.