Theater

Black History Month Legend – Lloyd Richards – Black Theater Matters

Born in Toronto, Canada – but raised in Detroit, Michigan – by Jamaican parents, Lloyd Richards was some of the vital figures in American theater within the second half of the twentieth century. He was the primary African American to direct a play on Broadway, a champion of greater than three generations of young actors, directors and playwrights, including the discovering playwright August Wilson. Richards helped develop the Pulitzer Prize winner’s voice by collaborating on Wilson’s significant early stage works and directed their acclaimed Broadway performances. Wilson’s stories chronicling the struggle of African Americans for dignity and respect, giving a voice to the boys and girls Richards and Wilson knew all too well from their humble pasts.

When he was 4 years old, Richards moved his family across the Canadian border to Detroit. There, his carpenter father found a job in one in every of the automotive factories. Richards was only nine years old when his father died, leaving his mother to boost five children alone within the depths of the Great Depression. The remainder of his youth was marked by poverty and hardship: his mother worked as a domestic employee to support her five children. Life became even harder for the Richards family when, two years later, Mrs. Richards became blind as a consequence of her doctor’s negligence. Lloyd, at just 13 years old, went to work shining shoes and sweeping floors at a barbershop to assist put food on the table. Later, as a student at Wayne State University in Detroit, Richards earned money as an elevator operator, taking his classmates to classes on the 4 floors of the Old Main Building.

The Richards family believed within the importance of education, and despite their difficult circumstances, he and his siblings were encouraged to check hard and go to varsity. He became involved in theater as a youngster and majored in it at Wayne State University. His studies were interrupted by World War II. He volunteered for a segregated division of U.S. Army fighter pilots often called the Tuskegee Airmen. After the tip of the war in 1945, he was in training.

After returning to Detroit, he sought out stage roles, working as a disc jockey, and helped start a theater company. With limited options for motion, Richards moved to New York in 1947. It was difficult to search out roles for African-American actors, but Richards found several roles on Broadway. In particular, he found employment within the dramas “Freight” and “The Egghead”. In the Nineteen Fifties, he found a job in radio, nevertheless it was more “secret”. Although Richards had a well-trained voice that conformed to the common Midwestern speech standard, radio productions took a risk in hiring him. If it were discovered that his radio work was handled by a black actor, programs throughout the South could be faraway from the air. The

In between off-Broadway roles, Richards waited tables and located a gentle job as an acting teacher at Paul Mann Studios. It was at this class that he met one other struggling actor, Sidney Poitier. Sharing their Jamaican heritage, Richards and Poitier formed a lifelong friendship. Poitier eventually introduced him to playwright Lorraine Hansberry, which led to Richards’ first exposure to directing. The play was titled “A Raisin in the Sun” and was a groundbreaking, original production that premiered on March 11, 1959 on the Ethel Barrymore Theater on Broadway. The show was nominated for several Tony Awards, including Best Director, and Richards received the excellence of being the primary African American to ever direct a play on Broadway.

Despite the success of “A Raisin in the Sun”, Richards found it difficult to provide one other hit. He directed the stage adaptation of Richard Wright’s novels “The Long Sleep” and “The Moon under Siege.” Both shows closed of their first week of performances. He then ventured into works that didn’t focus exclusively on African-American themes, equivalent to the 1965 musical adaptation of “The Yearling,” only to shut it the evening after opening. He was hired to direct a staged adaptation of James Baldwin’s The Amen Corner, but bumped into problems with the producers and was fired from the series.

Once again, Lloyd Richards has leaned on his past as a couch potato actor. In 1966, he became director of the actor training program on the School of the Arts at New York University. In 1968, he became director of the National Playwrights Conference on the O’Neill Theater Center in Waterford, Connecticut. The conference, held annually as a part of summer workshops, brings together a bunch of playwrights – some well-known, others emerging – to bring their latest work to its final version with the assistance of residents, a director and a playwright. Under his direction, O’Neill developed latest works by John Guare, Arthur Kopit, Wendy Wasserstein, Christopher Durang, and David Henry Hwang. African or African-American playwrights who created plays include Derek Wolcott, Wole Soyinka, Charles OyamO Gordon, Richard Wesley, Philip Hayes Dean, and most famously August Wilson.

He was a professor of theater and cinema at Hunter College in New York before becoming dean of the distinguished Yale University School of Drama in 1979. At the identical time, he became artistic director of the hugely influential Yale Repertory Theater.

Throughout his profession, Lloyd Richards sought to find and develop latest plays and playwrights, as a member of the Rockefeller Foundation’s Playwrights selection committee and the Ford Foundation’s New American Plays program, and as artistic director of the National Conference of Playwrights on the Eugene O’Neill Memorial Theater Center since 1968 until 1999. Richards’ long seek for a brand new, vital American playwright resulted within the 1984 production of August Wilson’s “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom.” In the Eighties and Nineteen Nineties, Richards directed productions of August Wilson’s multi-part chronicle of African American life at Yale Rep and New York. Shows on this series include “Fences,” Joe Turner’s “Come and Gone,” “The Piano Lesson,” “Two Trains Going” and “Seven Guitars.” They ended their skilled relationship in 1996 after the production of “Seven Guitars” on Broadway.

Richards’ television credits included segments on “Roots: The Next Generation,” “Bill Moyers’ Journal” and “Robeson,” a take a look at the lifetime of African-American actor and activist Paul Robeson, who was an early inspiration for the young Lloyd Richards. Richards also tackled Robeson’s life and legacy within the 1977 stage play “Paul Robeson.” Richards was the recipient of the Pioneer Award of AUDELCO, the Frederick Douglass Award, and in 1993 received the National Medal of Arts. He also served as president of the Association of Directors and Choreographers.

Richards retired from Yale in 1991 and from the O’Neill Center in 1999. He suffered from heart problems in his later years and died of heart failure on June 29, 2006, at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York. It was his 87th birthday. Survivors include his wife, Barbara Davenport Richards, a former Broadway dancer whom he married in 1957, and their sons, Scott and Thomas.

Theater

Article archive – essence Being

Theater

Article archive – essence Being

Theater

Arthur Mitchell, co -founder of The Dance Theater of Harlem, died

Cindy Ord/Getty Images

According to his niece Juli Mills-ross, a pioneer dancer and choreographer, Angel Mitchell, died of kidney failure on Wednesday morning. He was 84 years old. Born in Harlem in 1934, Mitchell grew up as one of the outstanding dancers within the Fifties and Sixties, because of his charismatic style.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Oxlshfuolzs

In 1955, Mitchell became the primary African American dancer from New York City Ballet (NYCB), to the good disappointment of some white patrons who complained when he was paired with white ballerinas. Despite this, the co -founder and artistic director of NYCB George Balanchine still gives Mitchella the chance of flash. Soon, Mitchell became a soloist and at last the primary dancer, who was the primary for a big ballet company on the time. After his term at New York City Ballet, Mitchell became a co -founder Harlem Dance Theater With Karel Shour in 1969. His primary goal was to open a faculty for young black people in the world where he grew up. Although many individuals thought that they were crazy about establishing a classic Uptown ballet school, under the leadership of Mitchell The Dance Theater of Harlem, he became one of a very powerful dance institutions in America.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wiqlmtataaw

According to a former dance critic Alan Kriegsman, “Mr. Mitchell not only launched and strengthened the career of many excellent dancers, but also changed the image of African -American dance professional.” Throughout his entire profession, Mitchell won several awards, each as a dancer and because the artistic director of the Dance Theater in Harlem. In 1993 he was honored by Kennedy Center of the Performing ArtsThe following 12 months through which he received the MacArthur Foundation “Genius Grant”. In 1995, Mitchell received National Medal of Arts. Mitchell, who described himself as Jackie Robinson from Ballet World, was powered by one goal: to interrupt down what many considered possible for the black people. “The myth was that because you were black, that it was impossible to do a classic dance,” he he said. “I proved that it is wrong.” Rest in peace.

-

Press Release1 year ago

Press Release1 year agoU.S.-Africa Chamber of Commerce Appoints Robert Alexander of 360WiseMedia as Board Director

-

Press Release1 year ago

Press Release1 year agoCEO of 360WiSE Launches Mentorship Program in Overtown Miami FL

-

Business and Finance10 months ago

Business and Finance10 months agoThe Importance of Owning Your Distribution Media Platform

-

Business and Finance1 year ago

Business and Finance1 year ago360Wise Media and McDonald’s NY Tri-State Owner Operators Celebrate Success of “Faces of Black History” Campaign with Over 2 Million Event Visits

-

Ben Crump12 months ago

Ben Crump12 months agoAnother lawsuit accuses Google of bias against Black minority employees

-

Theater1 year ago

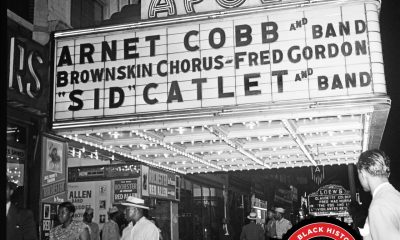

Theater1 year agoTelling the story of the Apollo Theater

-

Ben Crump1 year ago

Ben Crump1 year agoHenrietta Lacks’ family members reach an agreement after her cells undergo advanced medical tests

-

Ben Crump1 year ago

Ben Crump1 year agoThe families of George Floyd and Daunte Wright hold an emotional press conference in Minneapolis

-

Theater1 year ago

Theater1 year agoApplications open for the 2020-2021 Soul Producing National Black Theater residency – Black Theater Matters

-

Theater10 months ago

Theater10 months agoCultural icon Apollo Theater sets new goals on the occasion of its 85th anniversary