Whether it is a sting from a paper cut or trauma from combat injuries, wounds are woven into the tapestry of the human experience. Since precedent days, we have been fighting the enemy that lurks inside them – infection.

The constant threat of injury on the battlefield has prompted the search for brand spanking new ways to combat wound infections. However, early surgical procedures lacked the sterile instruments now available, which meant that for a few years surgery carried the additional risk of post-operative complications. wound infectionleading to numerous deaths.

Ancient practicesresembling using oils, mud, turpentine or honey to heal wounds, were common around 2000 BC Greek physician Hippocrates (460-377 BC) used vinegar clean the wounds and then bandage them to keep the dirt at bay.

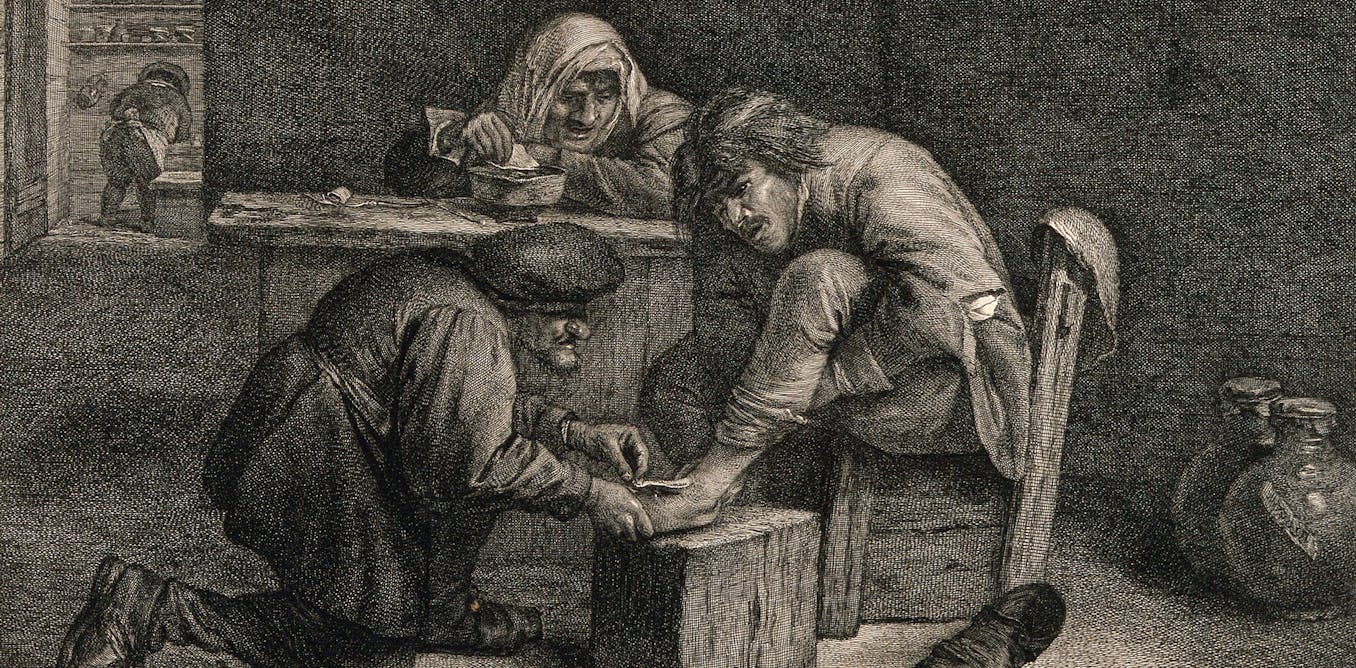

While there have been the first hospitals adopted in Europe in the Middle Ages, these were dangerous and brutal places. The rate of wound infections was high due to unsanitary conditions and the use of cauterization, which involved pushing burning iron into the patient’s wound down to the bone.

Wellcome Collection, CC BY

In the Eighties, pioneering surgeon Joseph Lister revolutionized the treatment of wound infections together with his introduction Bandages soaked in carbolic acid. And Robert Wood Johnson, founding father of Johnson & Johnson, produced first sterile gauze bandages by 1890. The combination of antiseptic and sterile bandaging marked a turning point in the evolution of wound care and infection control.

Discovery of penicillin by Alexander Fleming The 12 months 1928 was also a breakthrough in the treatment of wound infections. Until the Forties penicillin it was used to treat World War II soldiers who had wound infections that in previous years would have been considered fatal. For less serious wounds, the Lister approach to applying a dressing and antiseptic was still used.

Substances resembling silver AND iodine They have also been known for his or her antimicrobial properties since the nineteenth century. Iodine, although effective, caused pain and skin discoloration until safer and less painful preparations were developed in 1949. These preparations withstand modern dressings.

For on a regular basis cuts and scrapes, easy cleansing with water and applying an antiseptic cream will likely be enough. This helps prevent bacteria from by chance entering the wound, minimizing the risk of additional pain and swelling.

Although most wounds now heal easily, some do turn out to be infected. This was shown by research published in 2021 3.8 million people were treated by the NHS in 2017-2018, a rise of 71% compared to 2012-2013. These included surgical wounds, leg ulcers and burns. This shows how difficult it could actually be to treat wounds which are difficult to heal and are particularly susceptible to infection.

Challenges of contemporary times

One of the best challenges of contemporary treatment of wound infections is antibiotic resistance. This happens when bacteria develop the ability to overcome drugs designed to kill them. Treating resistant infections may be difficult and sometimes not possible.

Many bacteria have also turn out to be resistant to antimicrobial ingredients utilized in wound dressings. This is the case silver-based wound dressings, which are sometimes used to treat chronic wound infections. This sort of wounds is characteristic doesn’t cureand can remain an open, infected wound for a lot of months and even years. As well as having a devastating impact on people’s quality of life, it also places an enormous financial burden on the NHS.

The constant fight against wound infections is driving extensive research into latest, secure and effective treatments. Although progress is being made, the fundamental obstacle is that limitations laboratory testing methods. These tests, while essential to gain regulatory approval, often fail to capture the nuanced realities of wounds on the human body.

No two persons are the same and no two wounds are the same. This can lead to situations where a treatment works well in the laboratory but ultimately proves ineffective in real patients.

Creating wound models

Associated Press/Alamy

In response, scientists are overcoming the limitations of laboratory testing by creating more realistic synthetic wound models. Some even are 3d printing human skin (from surgical remnants) or animal skin, supplemented with artificial body fluids resembling pus. The goal is to create a model environment that more closely mimics real wounds.

Recently my very own Search party has made progress in developing laboratory models that behave like real chronic wounds when applied with antibacterial dressings. Although our models will not be perfect, they’re a step in the right direction, contributing to the development of formulations with promising potential for the treatment of wound infections in the future.

As we navigate the complexities of wound care, we proceed to seek latest, effective and secure treatments, driven by the efforts of scientists around the world. We are working towards a future through which the treatment of hard-to-heal wounds and infections is improved, improving each individual well-being and the efficiency of healthcare systems.