Lifestyle

Kidneys from black donors are more likely to be thrown away – a bioethicist explains why

As one in every of most important causes of death within the USA, kidney disease is a serious public health problem. The disease is especially severe amongst black Americans who are thrice more likely than white Americans for kidney failure.

Although blacks make up only 12% of the US population, constitute 35% in individuals with renal failure. The reason is partly the occurrence of diabetes and hypertension – the so-called two of the best authors for kidney disease – within the black community.

Almost 100,000 people within the USA they are waiting for a kidney transplant. Although black Americans are more likely to need transplants, they too less likely to receive them.

Worse yet, the kidneys Black donors within the US they are more likely to be kicked out for this reason faulty system which wrongly considers kidneys from all black donors to be more likely to stop working after transplant than kidneys from donors of other races.

As a scientist in bioethics, health, and philosophy, I imagine that this flawed system raises serious ethical questions on justice, fairness, and good stewardship of a finite resource like kidneys.

How did we get here?

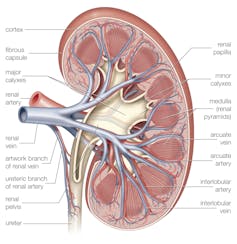

The US organ transplant system evaluates donor kidneys based on: kidney donor profile indexan algorithm that takes into consideration 10 aspects, including the donor’s age, height, weight and history of hypertension and diabetes.

Another think about the algorithm is race.

Research on previous transplants shows that some kidneys donated by black people are more likely to stop working sooner after transplantation than kidneys donated by people of other races.

This reduces the common patient retention time for a transplanted kidney from a black donor.

Encyclopedia Britannica/UIG via Getty Images

As a result, kidneys donated by black people are rejected at higher rates since the algorithm reduces their quality depending on the race of the donor.

It implies that some good kidneys may be wasted, which raises a variety of ethical and practical doubts.

Risk, race and genetics

Scientists have shown that races do social constructs which are poor indicators of human genetic diversity.

In the case of donor race, it was assumed that individuals belonging to the identical socially constructed group shared vital biological characteristics despite evidence that there was greater genetic variability inside racial groups than between other racial groups. This is the case with black Americans.

It is feasible that the reason for the observed differences in outcomes lies in genetics relatively than race.

People with two copies of certain forms or variants of the APOL1 gene are more likely to develop kidney disease.

About 85% of individuals with these variants won’t ever develop kidney disease, but 15% will. Medical researchers don’t yet understand what’s behind this difference, but genetics might be only a part of the story. Environment and exposure to certain viruses are also possible explanations.

People who’ve two copies of the file more dangerous types of the APOL1 gene just about all have ancestors who got here from Africa, especially West Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa. In the United States, such people are often classified as black or African American.

Kidney transplant studies suggest that kidneys from donors with two copies of APOL1 variants are at higher risk fail at higher rates after transplant. This could explain the information on the kidney failure rate of black donors.

How might this practice change?

Health care employees determine how to use and distribute limited resources. This comes with an ethical responsibility to use resources fairly and properly, which incorporates stopping the unnecessary lack of kidneys for transplantation.

Reducing the variety of kidney failures is vital for another excuse.

Brendan Smialowski/AFP/GettyImages

Many people agree to donate their organs to help others. Black donors may be concerned to learn that their kidneys are more likely to be thrown away because they got here from a Black person.

This practice can proceed reduce trust African Americans in a health care system that has long been suffering from mistreatment of black people.

Increasing the equity of organ transplantation can be so simple as: ignoring race when evaluating donor kidneys, as some medical researchers propose.

However, this approach wouldn’t explain the observed difference in transplant outcomes and will lead to the transplantation of some kidneys that are at increased risk of early failure due to genetic problems.

And because black kidney recipients are more likely to receive one kidneys from black donorsthis approach could perpetuate transplant disparities.

Another option that may improve public health and reduce racial health disparities is to discover aspects that lead to higher rates of failure in some kidneys donated by black people.

One way researchers are working to discover higher-risk kidneys is thru use APOLLO studywherein the impact of key variants on donor kidneys was assessed.

In my opinion, using variant as an alternative of race would likely reduce the variety of kidneys wasted while protecting recipients from kidneys that are likely to stop working sooner after transplant.

Ana S. Iltis, professor of philosophy; Carlson Professor of University Studies; and Director, Center for Bioethics, Health and Society,

This article was reprinted from Conversation under Creative Commons license. Read original article.