Sports

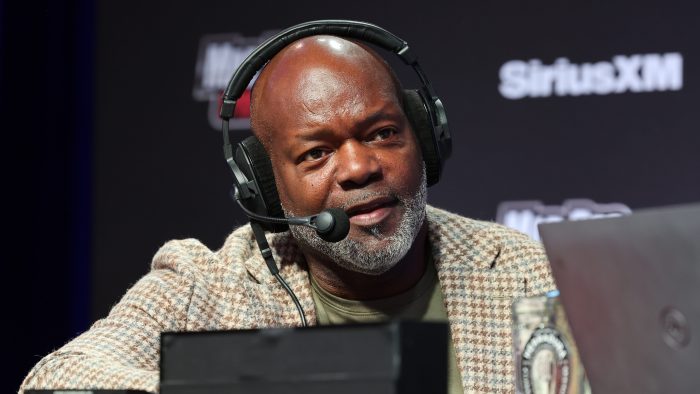

Why Emmitt Smith’s voice is so powerful after the DEI ban

One moment, football legend Emmitt Smith is there drinking beer with fellow Hall of Famer Peyton Manning. The next moment he is an advocate for diversity, equality and inclusion.

When University of Florida closed down its DEI officelargely as a consequence of A a bill signed into law in 2023 by Governor Ron DeSantis that prohibits state universities from spending money on diversity, equity and inclusion programsSmith responded with harsh criticism.

“I am completely disgusted by UF’s decision and the precedent it sets,” Smith wrote Sunday afternoon in a press release on X, formerly often called Twitter. “We cannot proceed to imagine and trust that a leadership team of the same ethnicity will make the right decision in terms of equality and variety. History has already shown that this is not the case.”

One might have a look at Smith’s Hall of Fame football profession and his penchant for being a pitcher and think he would don’t have anything to say about pressing civil rights issues. This narrative couldn’t be farther from the truth. Facing the stark challenges facing DEI programs at his alma mater, and with a deep sense of stability from history, Smith made a persuasive rebuke of policies inspired by politicians like DeSantis.

Smith’s position could appear unfathomable at the present time when athletes, current and former, care so much about public opinion and marketing dollars. But such comments should not just words from a bygone era, with baseball pioneers Jackie Robinson and Curt Flood, whose lawsuit against the MLB led to free agency. Similar statements were common just over three years ago when The murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police galvanized a generation’s demands for civil rights.

But why Smith? Why is he the NFL’s all-time leading rusher? Smith’s reasons are baked into his being.

Smith was born in 1969 in Pensacola, Florida – the same 12 months that city’s all-white Escambia High School was desegregated on federal orders. Escambia High School had a Confederate soldier as its mascot, flew the Rebel flag and the school song was “Dixie.” Protests by black students at football games and anxious residents led to a federal ruling in 1973 that banned the use of Confederate symbols and altered the mascot to the Raiders. The school board appealed the ruling in 1974, and in 1975 a federal appeals court overturned the order and remitted the case to the school board.

After students voted to maintain the mascot name Raiders, on February 5, 1976, a violent riot broke out at the school, resulting in described in March 1976:

“Years of racial hostility on this Florida city have erupted into violence in recent weeks over whether the local highschool sports teams can be called the Rebels or Raiders. Controversy over the name, which has been ongoing out and in of court for several years, sparked a riot at Escambia County High School on February 5. This afternoon, 120 Ku Klux Klan members in full regalia, but with their faces legally uncovered, paraded through the facility through the streets of Milton, a small town about 20 miles east of here. They arrived on the town in an 80-person caravan from outside Pensacola and called the march an “organizational effort.” Three Klan leaders from Alabama, Georgia and Florida attended the rally, which drew 450 people. “Four students were hit by gunfire during the school riot, 26 others were injured and $5,000 in damage was caused to the school during four hours of fighting, rock throwing and smashing of windows, trophy cases and other school property.”

Smith graduated from Escambia just over a decade later, in 1987.

Michael Wade/Icon Sportswire via Getty Images

American history, regardless of how joyful or wretched, is never too removed from the present. That’s why Smith’s criticism of his alma mater, the University of Florida, carries so much weight. It also helps, after all, that he’s the NFL’s all-time leading rusher.

“Rather than demonstrating courage and leadership, we continue to fail due to systemic issues, and with this decision, UF has adapted to contemporary political pressures,” Smith noted in his statement.

Birmingham, Alabama Mayor Randall Woodfin recalled the University of Alabama’s sordid history of segregation in his criticism of the state’s proposed anti-DEI law. He further said that if such laws is passed, he would encourage Black athletes and oldsters “attend other out-of-state institutions that prioritize diversity and inclusion“

“While I am Bama’s biggest fan, I have no problem with organizing activities for Black parents and athletes at other out-of-state institutions that prioritize diversity and inclusion,” Woodfin posted last month in X. “If supporting inclusion becomes a it’s an illegal state on this country, rattling it, you would possibly as well stand at the school door like Governor Wallace. Mannnn is Black History Month. You could have not less than waited until March 1st.

Let some say it, the most significant goalie in Alabama history was then-Gov. George Wallace’s segregationist stance at the school door, where he symbolically stood to dam two black students. And yet, like most of Wallace’s profession, it was a political stance and the students got here through.

All this uncertainty and anxiety doesn’t make life easier for school athletes, who find themselves at the center of a rapidly changing landscape as a consequence of the NCAA and name, image and likeness. On the one hand, it is interesting that after this era, NIL is on the verge of rapid development the order effectively limited the NCAA’s authority to punish athletes (and universities). At the same time, it is troubling to think that athletes are depending on institutions that don’t prioritize DEI.

It’s also price mentioning that we needs to be clear about terms like DEI and NIL, especially since people want them cut and dried. People hear “NIL” and think all college athletes earn cash. If this were the case, student-athletes wouldn’t compete the first $600 that comes their way. Thank you, EA Sports. People hear “DEI” and dismiss the intentions of diversity and equity initiatives, even when there is evidence to support it DEI is not so pro-black as you would possibly think.

Adam Gray/Getty Images

The solution for school athletes could also be much like GameStop’s motto – “power to gamers.” Just this week, March 5, Dartmouth basketball players voted to hitch the local unionwhich meant that athletes took public motion for the first time as employees.

We should work to support college athletes on all fronts, whether financially or socially. It is clear that they’re often pawns at the expense of billions of dollars in campus interests, whether on or off the field. We mustn’t only unlock their profession potential, but in addition their understanding of history and its connection to the present.

Or, as Smith put it at the end of his fascinating commentary: “And for those who think it’s not your problem and stand by and say nothing, you are complicit in supporting systemic problems.”